We are all living under extraordinary

times. We are also living with extraordinary situations – some created by us

and others over which we have no control whatsoever. The Supreme Court of India

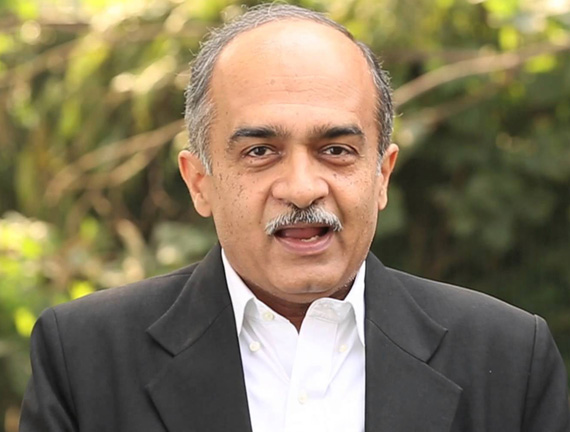

has created an extraordinary situation by holding guilty Prashant Bhushan, one

of its senior advocates, of contempt of itself. This situation was best avoided

by the honorable judges by being magnanimous.

True, the constitutional right to freedom

of speech would not stop the courts from punishing contempt of itself. However,

as explained by constitutional expert V.N. Shukla, “Judges have no general

immunity from criticism of their judicial conduct, provided that it is made in

good faith and does not impute any private motive to those taking part in the

administration of justice. “Justice is not a cloistered virtue,†said the Privy

Council in Ambard v. Attorney General for Trinidad and Tabago, “She must be

allowed to suffer the scrutiny and respectful, though outspoken, comments of

ordinary men.†(Constitution of India, by V.N. Shukla, 7th edition

published by Eastern Book Company, page 82.)

Shukla further pointed out the summary

jurisdiction exercised by superior courts in punishing contempt of their

authority exists for the purpose of preventing interference with the course of

justice. This is certainly an extraordinary power which must be sparingly

exercised but where the public interest demands it, the court will not shrink

from exercising it and imposing punishment even by way of imprisonment in cases

where a fine may not be adequate. This jurisdiction will not ordinarily be

exercised unless there is real prejudice which can be regarded as substantial

interference with due course of justice as distinguished from a mere question

of propriety.

In C.K. Daphtary v. O.P. Gupta (AIR

1971 SC 1132), the Supreme Court, in examining the scope of the contempt of

court, laid down that the test in each case is whether the impugned publication

is a mere defamatory attack on the judge or whether it will interfere with the

due course of justice or the proper administration of law by the court. A

distinction should be made between defamatory attacks on a judge and the

contempt of court.

Now what did Prashant Bhushan do? He

made two tweets. In the first tweet, posted on June 27, 2020, he wrote, “When

historians in future look back at the last six years to see how democracy has

been destroyed in India even without a formal emergency, they will particularly

mark the role of the Supreme Court in this destruction, and more particularly

the role of the last four Chief Justices of India.â€

In the second tweet on June 29,

Bhushan put out a photograph of the Chief Justice of India, S.A. Bobde sitting

on a motorcycle and wrote, “CJI rides a 50 lakh motorcycle belonging to a BJP

leader at Raj Bhawan Nagpur, without a mask or helmet, at a time when he keeps

the SC in Lockdown mode denying citizens their fundamental right to access

Justice.â€

The Supreme Court held that the two

tweets have the effect of destabilising the very foundation of this important

pillar of Indian democracy. It took umbrage at Bhushan linking the Supreme

Court to an Emergency-like situation and held his tweets false, malicious and

scandalous.

As pointed out by the Citizens for

Democracy, the tweets made by Bhushan were expressions of anguish felt by

thousands of victimized citizens who are at the receiving end of state power

and who cry for judicial protection. Holding him guilty and punishing him will

in no way promote administration of justice or enhance the majesty of law.

What is the way out? According to

Justice (Rtd) Kurian Joseph, “In both the suo motu contempt cases, in view of

the substantial questions of law on the interpretation of the Constitution of

India and having serious repercussions on the fundamental rights, the matters

require to be heard by a Constitution Bench.†It should also deliberate whether

a person convicted by the Supreme Court of India in a suo motu case should get

an opportunity for an intra-court appeal, since in all other situations of

conviction in criminal matters the convicted person is entitled to have a

second opportunity by way of an appeal.

(Published

on 24th August 2020, Volume XXXII, Issue 35)