A. J. Philip

A. J. Philip

.jpeg)

Leader of the Opposition Rahul Gandhi has always surprised me. Every time I go to Holy Family Hospital in Okhla, where my heart is periodically serviced, I remember him because it was there that he was born. I never believed the BJP's branding of him as Pappu, because I know that party has many a Pappu, even at the top. I know that the ruling party deliberately characterised him just the way Chandu in the Kerala folklore, Vadakkan Pattukal, was portrayed — jealous and treacherous.

It required eminent writer MT Vasudevan Nair to redeem Chandu as the legendary warrior in one of his films. In much the same way, he transformed the character of Bheema in his celebrated book 'Randamoozham,' where Bheema emerges as a considerate, loving and lovable character. Until then, he was always criticised for his impulsiveness, arrogance, and tendency toward excessive violence in conflicts.

In the case of Rahul, he did not need any external props. He found a place in the hearts of the people by the consistent manner in which he has been speaking against the anti-democratic traits of the Narendra Modi government.

The BJP stopped calling him Pappu when he went on a padayatra from Kanyakumari to Kashmir. I heard a well-known television anchor say at that time that once he crossed Tamil Nadu and Kerala, he would have to walk alone throughout the journey. But the anchor was wrong. Rahul attracted tens of thousands of people who thronged to see him all the way. His enthusiasm never diminished. Some BJP trollers even speculated that he was wearing a special, electronically heated garment to keep his chest warm as he walked during the severest winter, snowflakes falling on his bare neck.

The anchor was confident that he would abandon his journey on one pretext or another. Not only did he complete it, but he also undertook another journey from the east to the west of the country. No politician in India, including Mahatma Gandhi, has undertaken such journeys. And, one day, when he jumped into the Arabian Sea from a boat without any safety gear, I realised that he was an expert swimmer too. That is, perhaps, why he has been swimming against the current ever since he began leading the Congress Party.

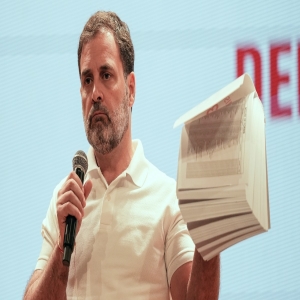

Last fortnight, Rahul dropped a political "bombshell" that virtually shook the nation. It happened just a day before the 80th anniversary of the American nuclear bomb, code-named The Little Boy, which was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Of course, Gandhi's bomb was not nuclear, but in terms of political effect, it was equally powerful. However, there was one fundamental difference between Rahul Gandhi's bomb and The Little Boy.

When America dropped the bomb in Hiroshima, it had to follow it up three days later with another one on Nagasaki. Nagasaki, it should be remembered, was the most Christian town in Japan, an otherwise Buddhist bastion. One of the targets of the bomb was the majestic Cathedral Church, whose spires penetrated the skies.

In Rahul Gandhi's case, there was no need for a second blast. His revelation was powerful enough to stand on its own. After all, he does not need teleprompters to make his speeches, and he does not shy away from meeting journalists — unlike another leader touted as a Vishwa Guru. As soon as he completed his presentation in English, a journalist asked him to repeat it in Hindi. He obliged him without a murmur.

He exposed how one Assembly segment in the Bengaluru Central Lok Sabha constituency — Mahadevapura — had over one lakh fake voters. These were not minor errors. Some voters appeared in multiple booths. Many had no proper address. Some had no photographs.

What's worse, as many as 50 voters "lived" in a single-room apartment. Others were far too old to be using Form 6, meant for first-time voters. There was not even one in the 18–21 age group who used Form 6, whereas there were many nonagenarians, octogenarians, and septuagenarians among its users. This large-scale fraud, Gandhi said, helped the BJP win the seat, even though it lost in the other five Assembly segments in the Lok Sabha constituency.

The question arose: why did he take so much time to come up with this revelation? The answer lies in the Election Commission's archaic practice — it provides only voters' lists in printable form. They cannot be electronically read. Whenever anyone mentions my full name in a post or article that can be accessed on the Internet, Google alerts me within seconds. That is because Google Guru indexes billions of pages.

Rahul asked why, in this age of advanced technology, political parties and citizens still get voter lists in an unreadable format. If they were electronically readable, one could instantly find out how many AJ Philips are registered as voters in the country. He also questioned why the Election Commission destroys CCTV footage of polling stations after 45 days.

Destroying footage, I must add, is like a murderer cremating the victim's body — it wipes away the evidence forever. A buried body can be exhumed and examined. Ashes provide nothing. In anthropology, skeletons buried for thousands of years have helped us understand evolution, but ashes thrown into the Ganga tell us nothing. In short, Rahul exposed the Election Commission's ugly underbelly.

Instead of addressing his allegations head-on, the Commission demanded that Gandhi submit an affidavit with evidence — citing a rule that is not even applicable here. That rule applies when someone's name is wrongly omitted from the list during the revision of the voters' list. Rahul, by contrast, used the Commission's own records to prove that its failures aided the BJP. With a click of a button, the ECI could verify the truth of his claims — for instance, that one gentleman's name appeared in multiple booths.

I wish Rahul and other Opposition leaders had gone further — demanding a special intensive revision of the Mahadevapura list, and insisting on an electronically verifiable version.

The ECI is constitutionally bound to revise the voters' list when there is a widespread belief that it is not genuine. It has just revised 8 crore names in Bihar in one month. At that pace, it could review Mahadevapura's 6 lakh voters in a few days. If the EC is convinced the roll is faultless, why resist a revision? If it were clean, such a review would prove Rahul wrong. Its refusal suggests it fears the truth.

If such dirty tactics were used in Mahadevapura, why not elsewhere? Remember the Varanasi counting, when Modi initially trailed the Congress candidate? Or Haryana, where the Congress was expected to win but lost by just 22,000 votes — enough to form the government?

The BJP holds power in Delhi because it won 25 more seats than the Opposition in 2024. If even a few were secured through Mahadevapura-style fraud, what moral right does it have to rule? The ECI must act to restore confidence in itself, for its independence is the foundation of democracy.

The government appears unconcerned. When the Mumbai terror attacks occurred, Home Minister Shivraj Patil resigned. After Pahalgam, Amit Shah stayed put — confident that electoral manipulation and communal propaganda would see the BJP through. It was with such confidence that Shah declared the BJP would rule India for the next 30 years. That was not a prediction but a challenge to the people.

All this must be seen in context. In late 2023, the law for appointing Election Commissioners was changed. The earlier panel included the Prime Minister, the Leader of the Opposition, and the Chief Justice of India. The new law removed the CJI and replaced him with a Union Minister nominated by the PM.

Ordinarily, the then Chief Justice should have protested. Instead, he was busy planning a puja at his house, to which he wanted to invite none other than Modi — the nation's most high-profile priest, having consecrated both the Ayodhya temple and the new Parliament building. Thus, the PM and his chosen minister — Amit Shah, in this case — could pick whoever they wished. The LoP became, at best, a scarecrow in the process.

Just before the 2024 elections, Election Commissioner Arun Goel resigned. On February 19, 2025, Gyanesh Kumar became the Chief Election Commissioner, joined by Dr. Sukhbir Singh Sandhu and Dr. Vivek Joshi — all handpicked by the government.

Gyanesh Kumar, an IAS officer from the Kerala cadre, became close to Amit Shah while in the Home Ministry, where he reportedly played a key role in scrapping Article 370 and reorganising Jammu & Kashmir. Later, he worked in the Ministry of Cooperation — also under Shah. In those days, journalists knew him as the "Kahwa man" for the tea he served. Now, all three commissioners are loyal to the ruling party — unsurprisingly unsympathetic to Opposition concerns.

The people saw their bias during the 2024 election campaign. The Commission did nothing when Modi made openly communal speeches, claiming Muslims would take away Hindu women's mangalsutra. Even a mild warning was too much for them to issue.

Rahul's focus was on fake additions, but deletions are just as worrying. In Bihar alone, 65 lakh voters — largely minorities and Dalits — were removed in the name of "Special Intensive Revision." The Supreme Court appears powerless to stop the ECI. Yet the remedy is simple: order the Commission to provide electronically readable voters' lists. Then, with one click, duplicates could be identified — like multiple Sanjay Kumars or Priya Kumaris with identical details in different places. Without transparency, India's boast of being the world's largest democracy is hollow.

A friend of mine in Delhi, with the family name "Thomas," found that all their names were deleted — except one, who happened to have a Hindu-sounding name. In the new India, it is not the Aadhaar card, ration card, or voter ID that proves your citizenship. It is your name. It is stories like this that give real-life shape to Rahul's larger warning: our elections are being manipulated. Unless the public demands action, democracy will be reduced to a ritual, stripped of meaning.

Rahul's "bomb" was not merely about Mahadevapura, nor was it just about one constituency's voters' list. It was about the slow, systematic corrosion of the electoral process — the one pillar of democracy that should be beyond partisan tampering. What he revealed is not just a statistic or a clerical lapse; it is the blueprint of how power can be perpetuated without consent, how victory can be engineered without votes.

When the Election Commission refuses transparency, when technology is shunned to keep scrutiny at bay, when the law is changed to capture the institution itself, the ballot box becomes a stage prop, not a safeguard of sovereignty.

In such a climate, Rahul Gandhi's act of calling out the rot is not merely political theatre — it is an act of democratic defence. The real test now is not for him, but for the people: whether they still have the will to demand the truth, or whether they will settle for the comfort of a managed democracy.