A. J. Philip

A. J. Philip

Twenty-five years ago, a European television channel came to interview me while I was with The Indian Express. The interview was based on a book by an Italian writer about the Pope of the 21st century. The author wanted to speak with me about the origins of Christianity in India and the role it played in the nation's development.

My editor, Shekhar Gupta, kindly allowed me to use his office for the interview. I was told that the author would travel across all continents—except, perhaps, Antarctica—to piece together his story about the future Pope. As I spoke under the arc lights in the Qutub Institutional Area office, with the Qutub Minar visible through the window, I expressed my hope that there would one day be a Pope from India.

Though my contact had promised to send me a copy of the video, it never arrived. Many months later, my relative in Germany—singer Stebin Ben's uncle—phoned to say that he had seen the episode in which I was featured.

Though I am not a Catholic, the Pope has always been a subject of great interest to me. This is partly because I grew up hearing stories about my maternal grandfather, PV Chacko. Despite never travelling beyond Pathanamthitta taluk in the then Quilon district, he journeyed all the way to Bombay to see and hear the first Pope who visited India.

That was Pope Paul VI, who came to Mumbai in 1964 to attend the International Eucharistic Congress. My grandfather travelled by train. Coincidentally, the orchestra group of singer KJ Yesudas, who was also on his way to Mumbai, was in the same compartment. They were so fond of my grandfather that they wouldn't let him pay for tea or snacks. He had many delightful stories to tell us about the Pope—how tens of thousands turned out to see him and the excitement of his motorcade.

I was surprised that a Syrian Orthodox Christian like my grandfather would take so much trouble to visit Bombay, even though both his sons—one a banker, the other a Central government official—lived there.

Years later, when Pope John Paul II came to India in 1986 and visited many cities, I was in Ranchi to report on his programme for The Searchlight, Patna, where I then worked. The Pope was accompanied by a plane-load of journalists, including my friend Jacobi of the Malayala Manorama, and I had to use all my ingenuity to send my report to Patna before the Pope's flight took off. From that point on, I followed his activities closely.

When the Pontiff visited India from November 5 to 7, 1999, my wife and I were present at the stadium in Delhi where he celebrated Mass. Later, I attended the all-faith reception held in his honour at Vigyan Bhavan, where I had the opportunity to shake hands with him. I admired him deeply, particularly for the quiet, yet powerful, ways in which he contributed to the fall of the Iron Curtain in Europe.

When George Weigel's 1200-page magisterial biography of the Pope appeared, I bought it and read it word for word. Even more fortunately, I had the chance to meet Weigel at the Centre for Policy Research in Washington, where he was a resident scholar, and interview him. At that time, I thought it was the finest biography I had read since James Boswell's immortal Life of Samuel Johnson.

The Indian Express sent me to the Vatican in 2000 to report on the Great Jubilee. Despite my friend and historian Fr Benedict Vadakkekara's best efforts to get me an audience with the Pope, I had to be content with meeting an archbishop. Instead, I would have loved to meet Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. I liked him for his strong views and his readiness to be called "God's Rottweiler."

When Pope John Paul II died, Ratzinger was my preferred candidate to succeed him. The Conclave seemed to agree when they elected Cardinal Ratzinger, who adopted the name Benedict XVI. He made history by becoming the first Pope in 600 years to resign, paving the way for Pope Francis.

When the Jesuit from South America became Pope, Babu Paul, a former IAS officer and Christian scholar, wrote a book on him, published by Media House. My wife was engaged to translate it into English. Alas, it never saw the light of day—mainly because of my own failings.

Pope Francis won the hearts of people worldwide by shunning ostentation and befriending the poor and destitute. One incident remains etched in my memory: he stepped out of his vehicle to lift up a security personnel who had lost his balance and fallen. Around the same time in India, a police officer collapsed and died while standing behind the PM. He did not even pause his speech and continued his verbal diarrhoea.

I was fortunate to be seated in the press gallery when Pope Francis canonised Mother Teresa as Saint Teresa of Kolkata. It gave me immense satisfaction, for I had once shaken hands with the Mother when she came to Bhopal in the seventies to inaugurate the Missionaries of Charity Centre. What's more, I had the privilege of sharing a meal with her. I was told she seldom dined in the company of men.

When Pope Francis became the first Pope to publish an autobiography—written with the help of a collaborator—I was among the first to buy, read, and review it in these columns. It was my way of expressing appreciation for him.

This time, when the Conclave met to elect a new Pope, I had no favourite. Recently, when I completed 50 years in journalism, some of my friends and colleagues gifted me "The Reluctant Dissenter: An Autobiography" by James Patrick Shannon. The book offered me a glimpse into the Catholic Church in America. Shannon, a bishop who attended the Second Vatican Council, later left the Church to lead a married life. He wrote the book on the 28th anniversary of his wedding.

Until then, all I knew was that America had produced only two Catholic Presidents—John F Kennedy and Joe Biden. I had also heard that there was an unwritten bar on an American becoming Pope, as the US, being a superpower, was seen as an unsuitable source for the papacy.

Nevertheless, there is no such formal restriction. The cardinals are free to elect any one of them. This time, 133 cardinals—the single largest number in history—participated in the Conclave.

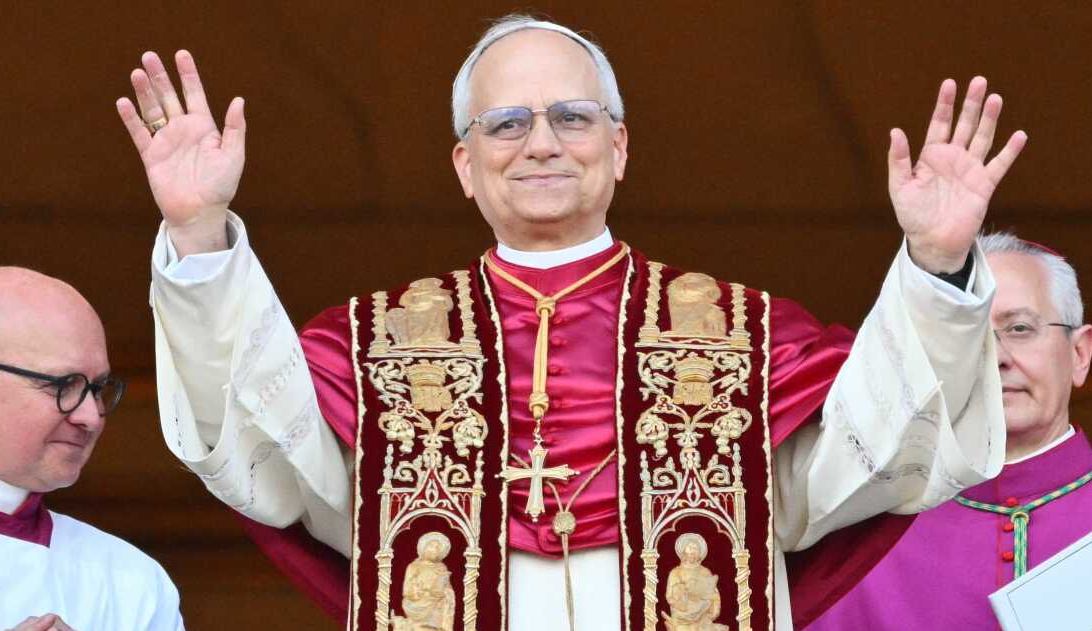

So, it was a bit of a surprise when Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost was elected Pope Leo XIV. The fact that he is an American was overlooked by his fellow Cardinals. Alternatively, they no longer consider America a superpower, as it no longer wishes to assume any of the attendant responsibilities.

Take, for example, President Donald Trump's statement when India sent missiles to nine locations in Pakistan and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. He called it "shameful" and said that the two countries had been fighting for a long time—something like 1,500 years. Poor Trump didn't know that Pakistan came into being only in 1947!

He has ended up on the world stage as something of a comic personality. On one occasion, he appointed someone to a federal post, and when asked why, he said the name came from someone. He hadn't even done a preliminary check of the person's antecedents.

In any case, the role of the US as the world's policeman has ended. So why deprive an American of a shot at the papacy? That's what the cardinals might have thought. Pope Leo XIV thus became the first American to attain that position. But then, he is more Peruvian than American. He served in Peru for a long time and was entitled to become a naturalised Peruvian. Now, as the successor of Peter, nationalities don't matter to him. He is first and foremost a citizen of the Vatican—the smallest state recognised by the United Nations.

I knew why Pope Francis chose that name. Although he was a Jesuit, he was more of a Franciscan at heart—someone who believed in the virtues of poverty and strove to emulate Francis of Assisi, whose prayer begins, "Lord, make me an instrument of your peace. Where there is hatred, let me sow love." That prayer is second only to the Lord's Prayer that Jesus taught his disciples.

As the new Pope served in Peru while his predecessor was a priest, bishop, archbishop, and cardinal in neighbouring Argentina, they knew each other for a long time. And they were also very friendly. The New York Times today (May 9) carried a long interview with the Pope's elder brother, John Prevost. He lives in New Lenox, a tidy city of 27,000 people about 40 miles southwest of downtown Chicago.

Leo—whom Mr Prevost is accustomed to calling Rob—"has great, great desire to help the downtrodden and the disenfranchised, the people who are ignored," he said. He predicted that his brother would carry on the legacy of his predecessor, Pope Francis. "The best way I could describe him right now is that he will be following in Francis's footsteps," Mr Prevost said. "They were very good friends. They knew each other before he was Pope, before my brother was even a bishop."

Mr Prevost said he usually spoke with his brother by phone every night, but hadn't talked to him since the Conclave began. He described the new Pope as "simple, really. He's not going to go out for a 19-course meal." Last August, Mr. Prevost said, his brother stayed with him at his home in New Lenox for a few weeks. They have another brother who lives elsewhere in America. Their father, Louis Prevost, was a school superintendent, and their mother, Mildred Prevost, was a library assistant.

Why did he choose to be known as Leo? My brief research suggests it was a clear and deliberate reference to Pope Leo XIII, who led the Church during a turbulent period and helped guide it into the modern era. Leo XIII—who served from 1878 to 1903, one of the longest papal reigns in history—is remembered for vigorously defending the rights of working people to a living wage and for laying the foundations of modern Catholic social teaching. He earned the title "the Pope of the workers."

Leo XIII is often seen as a bridge between the pre-modern and modern Church. He was a strong leader, deeply engaged with the issues of his time. He responded with both authority and compassion to the challenges of the industrial age, advocating for workers' rights and supporting the legitimacy of labour unions. By choosing the name Leo XIV, the new Pope may be signalling his own intent to grapple courageously with the defining issues of our era.

Leo XIII began his pontificate after the Papal States—once ruled by the Pope for centuries—were annexed by a newly unified Italy in 1870. Though the papacy had lost its temporal power, he worked to reaffirm its enduring moral authority across national boundaries. Leo XIII also fostered deeper devotion to the Virgin Mary, penning 11 encyclicals on the rosary, which he viewed as a powerful spiritual practice.

In a symbolic gesture, Pope Leo XIV concluded his first address by reciting the rosary, evoking that same spirit of Marian devotion. Leo XIII was also the first Pope to appear on film and established the Vatican Observatory to demonstrate the Church's openness to scientific inquiry. "It must be clear," he once wrote, "that the Church and its pastors do not oppose true and sound science, both human and divine, but that they embrace, encourage and promote it with all possible zeal."

In choosing to follow in the footsteps of such a visionary predecessor, Pope Leo XIV seems to be embracing a legacy of moral clarity, intellectual openness, and social concern. One can only hope he will meet the challenges of the 21st century with the same courage and conviction.