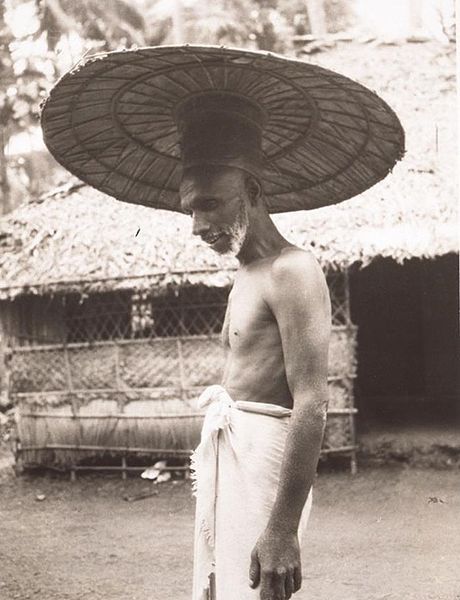

.jpg) N. Kunju

N. Kunju

When a person is 90 or above, an early part of life becomes history.

I was born in 1929. World War II (1939-’45) started when I was 10, and it ended when I, then 16, was about to end my studies in school. My juvenile years were the war time and the period struck poor Indians the worst. All resources and essential materials went to the war effort, be it food or fuel. That left places like Bengal to famine and death by hunger.

Mine was a village in the princely state of Cochin, now in the Malayalam-speaking Kerala state. But then, Cochin was my country and the Maharajah was our God. The first lesson of Class 1 text used to be a poem (in Malayalam) beginning:

“Who is the king, my mother?

He is God, my son.”

Our kings used to be kind and very old when they ascended the throne after a long chain of deserving candidates died. That was one reason they were not aggressive and adventurous, and beneficial to us too, young school children. The benefit was they died soon and we got a holiday frequently.

All families in the village were farmers except one or two like mine whose head was a government servant with a salary of about Rs. 15. The farmers lived comfortably with the rice they harvested, a part of which they sold for high war-time prices and the rest they kept for own consumption. The low-salaried employees were struck with scarcity. People were accustomed to eating rice only, but there was no rice in ration shops. Instead, wheat or imported maize was supplied. People did not know how to cook them. They boiled the wheat and maize, and reluctantly ate the stuff.

Women were the worst victims of war though they didn’t risk the killings and maiming on the fighting front. Kerosene disappeared from shops and they had to cook with firewood gathered from forests miles away. Rows of women with long bundles of firewood on head could be seen in the morning on the road to homes and sometimes to the town to sell. As a boy on school holidays, I remember I used to go to the forest with my mother and carry a small bundle of firewood home. Of course, the forest was near to the village. Now there is no forest around and my village and the forest have been devoured by the town.

Motor transport was limited to buses. There was no petrol available. Buses appeared with a big cylinder attached on the back in which charcoal was burnt to make gas that was taken to the cylinders of the engine for combustion. The driver, conductor and the cleaner had to work early morning for hours to start the vehicle, and make it roadworthy. Anyway, children walked four or five kilometres to school in town. I had never got into a bus during school days.

Many young men had joined the Army, or the workforce meant for building roads etc. in distant lands for war effort. There were no phones those days and the fastest communication that reached home was a telegram. That most probably would be to intimate somebody’s death. Even if it were someone announcing his coming home shortly, there would be no one to read it and his people would start wailing till someone like me read and interpreted it for them. Yes, I was the only one there going to school and could read English.

The farmers in the village found no use in sending their children to school some five kilometres away in town; the boys could be of help in tilling land. The illiterate families made use of my services to read and write letters to their dear ones in distant land. They gave me one anna (one-sixteenth of a rupee) for the service. Especially young wives who wanted their letters to husbands to be kept secret dictated to me what to write; they had full confidence in me not to divulge the contents to their mothers-in-law. They gave me two annas and gifts when their husbands came home on leave. These sundry earnings helped me to buy lunch in town on schooldays, which otherwise I had to forgo.

There was a village library nearabout and I was a voracious reader especially of short stories of modern Malayalam writers Pottekkat, Thakazhi, PonkunnamVarkey and Basheer. Inspired by them, I wrote some 5 stories and gave a heading Nammude Paavangal (Our poor) and gave it to the Electric Printing Works in town with no hope of getting published. To my pleasant surprise, the manager called me and said it would be published. He had got it assessed by my Sanskrit teacher K.K. Raja who had recommended its acceptance. That was the only Malayalam book I wrote that too while studying in school. I got a royalty of Rs.20 which I gave to my father who was surprised to know I earned more than his salary for a book.

Those were the years of turbulence and national awakening. Gandhiji had called the British to quit India. He and other Congress leaders were jailed. There were meetings and agitations in the urban areas against the British Raj.

Some students of the college attached to my school (St. Thomas, Trichur) took out a procession to the Central Jail, Viyyur, located near my village. I was on my way back from school and saw an elderly friend in the procession that was shouting slogans to release political prisoners in jail. I too joined the procession, clutching books in my hand. Soon the leader of the procession spotted me and pointed out that I was underage and could not join the agitation. I was disappointed, but was spared the severe lathi-beating by the police, a few miles ahead. The processionists lay down on the road and were rudely dragged to the police van. In the police station, their names were noted and were let off with a warning.

Those lists helped them later to be recognised as freedom fighters and earned them pension and Thamrapathra. Though spared of the beating, I was deprived of the status of a freedom fighter for life. However, later I got the Independence medal from the Army for being in service at the time of India attaining freedom, August 15, 1947. That of course is another story.

I passed matriculation as the war ended and there was no scope of entering college. There was no work and no way to earn. I wrote another book of stories and gave it to the press. It was returned as K.K. Raja opined it was too revolutionary with Communist ideas. I was thoroughly frustrated and threw the manuscript into the river on my way back home. That was the last Malayalam book I wrote.

The change from a student to an unemployed young man made me sort of guilty conscious. There was no possibility of getting a job in the state. I left to Madras (now Chennai) by train where I had a relative employed and became his unwelcome guest. I walked around the city seeking a job. There was I on the road in the hot summer sun clad in dothi and shirt and barefoot. I could speak English, but seeing my condition, no one entertained me in posh offices in the multi-storey buildings.

Days of wandering brought me to the Army recruiting office. There was a crowd of young men, healthy and muscular, undergoing tests in various stages of undress. Seeing them I lost hope. Anyway, I ventured to a Havildar who eyed me with pity. But the matriculation certificate I extended made all the difference. Matrics were hard to get those days. He took me to the Recruiting Officer who sent me straight to the medical officer. After inspection, he said I was all right but for shortage of weight. “Weight will be made up,” said the recruiting officer. I was enrolled and a movement order was made to the Army Ordnance Corps Training Centre, Ferozpore (Punjab). A military special was to start in the evening and I was to get into it. I went to inform my host about the job, collected my bag and got into the special train.

I was enrolled in the British Indian Army in June 1947, and India got independence in August. When I boastfully wrote this to a friend, he replied: “With soldiers like you, the British must have realised they couldn’t defend their colony any more.”

(The writer is an ex-serviceman, journalist and author. He served both the British Indian army as well as free India’s army)