.png) Jaswant Kaur

Jaswant Kaur

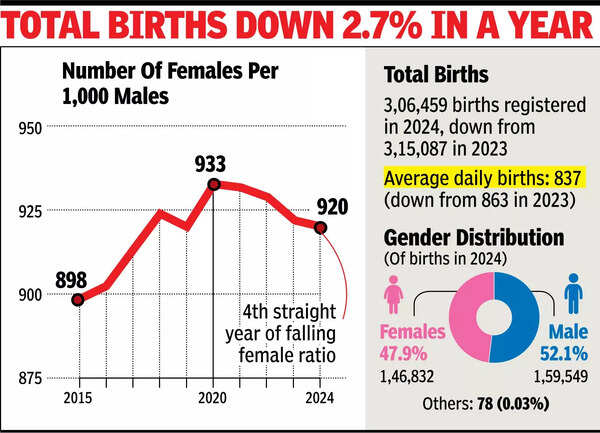

Some stories are written not in words but in numbers. And sometimes these numbers whisper truths that are too heavy to be ignored. You may wonder what these metaphors are about. This can be easily related to the data published in the latest Annual Report on Registration of Births and Deaths in Delhi (2024), prepared by the Directorate of Economics and Statistics and the Office of the Chief Registrar (Births & Deaths).

It suggests that Delhi's sex ratio at birth has declined to 920 girls for every 1,000 boys from 922 in 2023 and 929 in 2022. The dip may appear nominal, but when extrapolated to the number of children born, it becomes enormous. It shows that hundreds and thousands of girls have been denied their right to be born. Their existence has been erased. An age-old tradition or prejudice has been upheld silently in an era that boasts newer technologies and innovative ways of economic growth.

For a city that calls itself modern, global and forward-looking, the numbers speak volumes about its bias towards boys. This is not some remote district or village struggling against entrenched traditions. This is our national capital - the place where policymakers set the agenda, where global universities and activists gather, and where some of the most empowered women in the country lend their voices to the voiceless. Yet, beneath this veneer of prosperity and aspiration, our daughters are quietly being made to disappear.

For some, it might be easy to reduce this problem to one cause - sex-selective abortions enabled by clandestine diagnostic centres in the city. Of course, they do play a major role. The Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act has been in place for nearly three decades, yet enforcement remains inconsistent.

The evolution of newer technologies, particularly non-invasive methods, has made sex determination easier and harder to track. That such clinics operate with impunity is hardly a revelation. We all know how collusion between families and medical professionals ensures that this cycle of silent deaths is kept alive. But the story does not end at the ultrasound machine.

The bias runs deeper. Girls, even when born, often face a battle for survival. The National Family Health Survey-5 shows that infant and child mortality remains higher among girls than among boys. People usually tend to prioritise feeding their sons first, seek medical help sooner for boys, and invest more in their growth. No wonder girls are often enrolled in government schools, while boys are admitted to private schools despite limited resources.

The discrimination is not always overt. It lurks in everyday choices. From a mother breastfeeding her son longer to a father willing to spend more on a son to a grandmother quietly wishing for a grandson next time, these choices perpetuate a quiet and silent form of violence that is glaringly revealed in the form of statistics or reports like the one before us.

At times, we believe that education helps us overcome the inherent biases that have been passed down from one generation to another. They are a sobering reminder that knowledge alone does not always change behaviour. Such prejudices run deeper, demanding far more than classrooms and degrees to be undone.

It also shows that urban modernity has not softened this bias either. In fact, it seems it has only sharpened it. Most families aspire to have a better standard of living with smaller family sizes. This upward mobility comes at a cost, as many households aim for one or two children. In such circumstances, pressure to ensure one of them is a boy intensifies. Migrant populations from Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar, where patriarchal norms are deeply entrenched, reinforce these preferences. Instead of becoming a corrective force, Delhi has become an amplifier of these inherited prejudices.

The government, whether at the central or state level, has introduced various schemes. Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (BBBP), launched in 2015 with the explicit aim of correcting declining child sex ratios, brought unprecedented attention to the issue. From TV screens to newspaper headlines, to school buildings, book covers, and even wedding invitations, the slogans promoting the scheme gained widespread popularity almost overnight.

In some districts of Haryana, improvements were visible. Yet, as the Comptroller and Auditor General's 2022 report showed, nearly 80 per cent of the funds allocated to BBBP were spent on publicity rather than substantive interventions. It showed that mere awareness cannot result in behavioural change.

Another scheme that warrants mention is the Sukanya Samriddhi Yojana. It offered a direct nudge with tax-free savings and a higher interest rate. It aimed at incentivising investment in the future of girls. However, it remained attractive only to middle-class families with some disposable income. The poor, who mostly struggle to make both ends meet, have not benefited from this scheme. Similarly, Delhi's Ladli Scheme, which offers cash transfers at various milestones during a girl's life, has remained inaccessible due to bureaucratic hurdles and low awareness. The intent is laudable, but the impact remains limited.

This only means that, despite the intent to solve the issue, policies may not be effective unless they are prepared with consideration for the most vulnerable and underserved communities. Furthermore, a great deal more needs to be done to undo centuries of cultural conditioning.

Even today, the son is still seen as the one who will carry the lineage forward, inherit property, and perform the last rites. The daughter, meanwhile, is still too often viewed as "paraya dhan," destined to leave the house, burdened with the shadow of dowry, illegal though it might have been. As long as these ideas endure, we cannot expect that savings schemes or catchy slogans alone will transform the landscape.

However, we cannot afford to ignore this huge imbalance. We have seen how skewed sex ratios in Punjab and Haryana have created "marriage markets" where women are bought, trafficked, or shared between men. Violence against women is higher where women are fewer. Delhi, with its falling numbers, is on a similar path. An unnatural shortage of women will not only destabilise demographics but also corrode the social fabric. A society that cannot value its daughters equally will struggle to build relationships of trust, compassion and equity.

The solutions, therefore, must be multi-pronged. The PCPNDT Act, though well-intentioned, has suffered from weak enforcement. Its promise can only be realised through rigorous monitoring and penalties for errant clinics. Unfortunately, the conviction rate under the act has remained abysmally low since its inception, sending a dangerous message to perpetrators that they can go unpunished even if caught red-handed.

We need structural reforms, not tokenistic schemes. It is essential to revamp our policies to ensure that education subsidies effectively reach girls at the edges. Our health insurance needs to be designed to cover maternal and child health. Not only this, but it is also vital to design vocational opportunities for girls to make them visible contributors to prosperity, rather than being perceived as a financial burden. Besides, we need to invest in gender education and sensitisation, beginning from the school itself, to ensure cultural transformation.

When the nation's capital records a declining sex ratio, the message to the rest of India is bleak. It shows that even in the heart of governance and activism, daughters are still denied the right to be born. If change cannot be demonstrated in the national capital, where else can we expect it to take place?

Every missing girl is not merely a deficit in statistical data; it is a story about a missing doctor, teacher, artist, entrepreneur, or leader. It is about a missing voice that could have shaped debates, a mind that could have solved problems, a soul that could have loved and been loved. To reduce her to a number is already an injustice; to erase her altogether is a national betrayal.

We are failing our daughters. And unless we confront this uncomfortable truth, the demographic future we are building is not only unequal but also unstable. Delhi's declining sex ratio cannot be dismissed as just another statistic in an annual report. It is a moral alarm bell demanding urgent action. Whether we choose to confront it or ignore it, our response will shape not only the future of our daughters but also the destiny of a nation that aspires to be a Viksit Bharat by 2047. And how can we hope to achieve that vision if half our children are denied the chance to be born?