.png)

Four decades ago, I arrived in New York City as a scholarship student at Fordham University, Bronx—wide-eyed, hopeful, and determined to earn an MA degree in Mass Communication and Journalism. Among my fellow scholars was a young man from a village in Uttar Pradesh. He had never left India before.

Within weeks, the cultural vortex of New York City, Manhattan's 42nd Street, swallowed him whole. He struggled to adapt, didn't make the grades, missed classes, and had to return home. I stayed, completed my MA degree, followed it with a second in Religious Education, and later became the youngest editor of The Herald weekly in Calcutta and the first non-Italian director of the Salesian News Agency in Rome—admired for my American education, but not immune to the whispers.

"Furbi Indiani," my Italian colleagues would say—clever Indians. Not always admiringly. The phrase carried a sting, often surfacing in conversations about scams and shady dealings. One story involved Indian-origin scamsters in London who used a metal coin tied to a string to activate free ISD calls from public telephone booths to Punjab. Ingenious, yes. Illegal, certainly.

Scams, Counterfeits, and Moral Compromise Corrode India's Reputation

Years later, as a PhD student at the Salesian University in Rome, I asked a Nigerian classmate why his countrymen in India were often associated with big-time scams. He looked at me, half amused, half blunt: "Because you people are foolish. You fall for idiotic promises of legacy money."

That moment stayed with me. It wasn't just about Nigeria or India. It was about the global perception of cunning—how some communities become synonymous with deception, and how that perception is shaped by real, recurring patterns.

Even Mother Teresa of Kolkata was not spared. In the 1980s or early 1990s, fraudsters reportedly opened a bank account in Hong Kong under the name of the Missionaries of Charity. Their aim? To intercept and process donation cheques meant for the saint's work in Calcutta. It was a chilling reminder that no institution, however revered, is immune to the reach of deception.

Shadow Economy: Imitation, Manipulation, and Transnational Crime

Today, the phrase Furbi Indiani feels more relevant than ever. From counterfeit toothpaste factories in Gujarat to billion-dollar laundering networks in Singapore, Indian-origin individuals and companies are implicated in scams that span continents and industries. This is not a sweeping indictment of a nation's people—but a call to confront the shadow economy that thrives on imitation, manipulation, and criminal moral compromise.

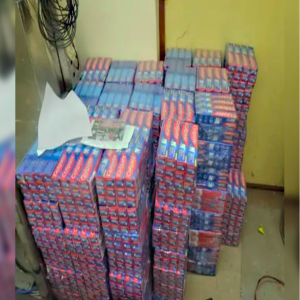

Take the October 2025 raid in Gujarat's Chitrod area of Rapar taluka, where police uncovered a factory producing fake Colgate toothpaste, Sensodyne, Eno, and even Gold Flake cigarettes. The unit, run by one Rajesh Makwana, was churning out counterfeit goods using substandard ingredients and packaging designed to mimic the originals. Goods worth ?9.43 lakh were seized. This wasn't just a local scam—it was a health hazard.

Trust Turns Toxic: Cough Syrup Deaths

In October 2025, over 20 infants in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan died after consuming contaminated cough syrups laced with diethylene glycol—a toxic industrial solvent. The syrups, distributed under names like Coldrif and manufactured by Indian firms, were found to contain lethal impurities. One of the companies, Sresan Pharmaceuticals, was flagged for gross negligence. Another, Kayson Pharma, had supplied the syrup through government channels. The World Health Organisation issued global alerts. But the damage was done. Tiny lives were lost to greed.

This wasn't just a regulatory failure. It was a moral collapse. We are no longer talking about scams—we are talking about crimes against humanity.

Ulhasnagar Jeans to Singapore Bank Mules

But this culture of deception didn't begin yesterday. In the 1970s and '80s, the label "Made in USA" carried prestige—except in Ulhasnagar, Maharashtra, where it stood for the Ulhasnagar Sindhi Association. Enterprising traders from the Sindhi community, displaced by the Partition and resettled in refugee camps, began branding locally made jeans, shoes, pens, and electronics with "Made in USA" tags to exploit India's appetite for foreign goods. Ulhasnagar became synonymous with spurious brands—Wrangler jeans that faded in a week, Reebok shoes that peeled after a jog.

In Chennai, the Enforcement Directorate exposed a ?120 crore trade-based money laundering racket. In Dubai, an Indian-owned firm defrauded suppliers of goods worth ?29 crore. In Singapore, two Indian-origin men were charged in a $1.1 billion scam.

Visa Frauds and Human Trafficking

In the US, in 2024, three Indian-origin men—Kishore Dattapuram, Kumar Aswapathi, and Santosh Giri pleaded guilty to manipulating the H-1B visa system. They created fake job offers and shell companies to secure visas for tech workers. While some may argue these actions stem from desperation or broken systems, they nonetheless reflect a pattern of calculated deceit.

Perhaps the most chilling revelation came from Tamil Nadu police in September 2024. A cyber scam network operating out of Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia siphoned ?10,188 crore from India. Indian nationals were trafficked on tourist visas and forced to work in scam compounds—wire-fenced facilities where they executed phishing attacks and financial frauds.

Why Value Formation is a Must in Vocational Training

The Furbi Indiani thrive because of systemic gaps: weak enforcement, low consumer awareness, digital anonymity, and cross-border complexity. They are not innovators. They are imitators who corrode trust, endanger lives, and damage India's global reputation.

As Fr Joseph Podimattam, Director of Don Bosco Technical Institute, Kolkata, rightly puts it: "We aim to form not just skilled professionals, but responsible citizens rooted in values." That formation is the antidote to the Furbi Indiani syndrome.

India's entrepreneurial spirit is a gift. But it must be tempered by conscience. The Furbi Indiani may be clever—but cleverness without character is a recipe for ruin.