.jpg) Jose Vattakuzhy

Jose Vattakuzhy

The ILO's Global Employment and Social Trends 2026 report, published on January 14, 2026, highlights some contradictions. It states that, amid top-level, low, and stable global unemployment, job quality is getting worse, and the progress toward decent work has stalled. Unemployment is projected to stay at 4.9 per cent, affecting about 186 million people, yet a significant jobs gap of 408 million still exists. Working poverty is common, with 284 million workers living on less than 3 US dollars a day.

Informal employment is rising again and is expected to reach 2.1 billion workers by 2026. Youth unemployment and inactivity are on the rise, women continue to face serious participation gaps, and the shift toward higher-productivity, formal jobs has slowed. At the same time, AI-related risks and global economic uncertainty threaten future wage growth and job opportunities.

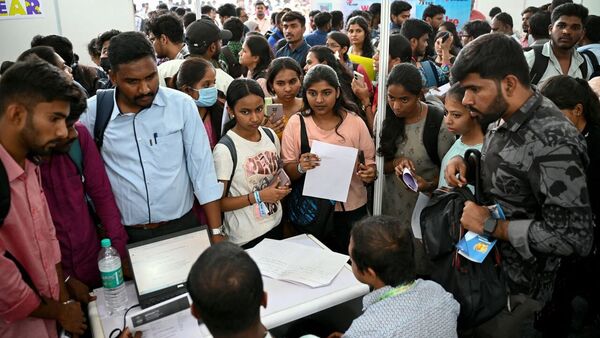

These trends are evident in the Indian labour market. India's job growth mainly comes from demographic changes rather than improvements in job quality, like secure contracts, better pay, or social protections. While labour force participation has increased, especially among women, most of the new jobs still fall into informal, own-account, and casual employment, reflecting the global trend noted by the ILO.

Employment Growth without Decent Work

The ILO expects modest global employment growth in 2026. Low and lower-middle-income countries, like India, will see this growth mainly due to population changes, not productivity gains. India's working-age population has increased significantly, rising from 61 per cent in 2011 to 64 per cent in 2021. It is projected to reach 65 per cent by 2036. A large number of jobs need to be created because of this influx of workers, often outpacing the growth of high-skill, productive jobs.

India exemplifies this trend. Every year, millions enter the labour market, but the economy struggles to create enough good, secure jobs. Therefore, employment growth often consists of self-employment or casual work due to necessity. Short-term wage labour, particularly in the service and IT sectors—including gig work—lacks formal protections. This situation supports the ILO's warning that job numbers alone hide serious problems in job quality.

Rising Informality as the Dominant Trend

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) predicts that by 2026, around 2.1 billion workers worldwide will be in informal jobs, with the fastest growth happening in Southern Asia. India is a major contributor to this trend, with 80 to 90 per cent of its workforce involved in informal or semi-formal work. Most of these workers do not have written contracts, paid leave, or social security, even though this sector generates about 50 per cent of the country's GDP.

In India, informality is present in construction and manufacturing through contract labour, in agriculture through disguised unemployment, and in urban services through gig platforms, delivery work, and domestic help. This issue affects women and young people disproportionately, with around 94 per cent of women workers and nearly 98 per cent of youth aged 15 to 24 engaged in informal jobs.

The ILO notes that informality is linked to low wages, weak social protection, unsafe working conditions, and limited collective voice, which continue to shape the work experience for most Indian workers.

Working Poverty and Stagnant Labour Incomes

Even though India is growing into the world's third-largest economy, real wages for many workers, especially those in informal, migrant, or rural jobs, have not kept pace with rising living costs. Real incomes were further hurt by the inflation spike from 2022 to 2025, and wage recovery has been uneven. The top 1 per cent owns about 40 per cent of all wealth, while the top 10 per cent controls nearly two-thirds. This creates a stark contrast between the rich and the poor. As a result, the richest 10 per cent of people receive 58 per cent of the country's revenue, while the poorest 50 per cent get only 1 per cent.

The ILO's finding that the global labour income share remains below pre-pandemic levels is particularly relevant in India. Capital-intensive growth and weak labour organisations limit workers' ability to benefit from productivity gains.

Concerns and the Crisis of Youth Employment

The ongoing crisis young workers face is one of the most concerning trends the ILO has identified. Despite their education and training, nearly 257 million young people worldwide are unemployed, with youth unemployment still exceeding 12 per cent.

This issue is mirrored and exacerbated in India, where young people are shut out of the labour market, rural youth migrate to cities only to find precarious employment, and even aim abroad, and educated youth face jobless growth and credential inflation.

The ILO warns that extended youth exclusion could result in a lost generation, jeopardising social cohesiveness and long-term economic potential if prompt action is not taken.

Gender Inequality in the World of Work

The ILO highlights ongoing gender gaps in employment. Women make up only two-fifths of the global workforce. India, in particular, has one of the lowest female labour force participation rates among major economies.

Women in India mainly work in unpaid care roles, family labour, and low-paid, informal jobs. These include home-based work and piece-rate jobs.

The female labour force participation rate is around 32.8 per cent, while the male rate is 77.2 per cent. There is also a significant gender pay gap of 20 to 30 per cent. These inequalities show in India's ranking of 127th out of 146 countries in the 2023 Global Gender Gap Report. The ILO believes these differences stem mainly from deep-rooted social norms, weak institutions, and insufficient care infrastructure, rather than just economic issues.

Technology, Artificial Intelligence, and Unequal Shifts

While artificial intelligence and digital technologies are often seen as ways to boost productivity, the ILO warns that their disadvantages have not been widely realised. The threats of job disruption are real, especially for young people and those in entry-level jobs.

In India, automation threatens typical clerical and service jobs. Meanwhile, platform work is growing without proper labour rights, and many rural and informal workers face digital divides. The gig economy, which depends on platforms, is booming. The number of workers is expected to jump from 7.7 million in 2020-21 to 23.5 million by 2029-30. Yet, internet access in rural areas is only 37%, compared to 64% in urban areas, leading to a "two Indians" scenario. Without proactive regulation and reskilling, technological advancements might worsen labour market inequalities rather than improve them.

Structural Transformation at a Standstill

A central point of the ILO is that improvements in decent work are linked to workers moving from low-productivity jobs into higher-productivity sectors. However, the report notes that this process of structural transformation has slowed significantly worldwide.

India's experience reflects this global trend. Manufacturing has not managed to absorb a large number of workers, while services growth has been very uneven, focusing on high- and low-skilled jobs. At the same time, agriculture still holds a large pool of surplus labour. Unlike the economies in East Asia, India did not have a strong period of manufacturing-led growth that could create large-scale, formal, high-productivity jobs. Instead, employment has shifted mainly from agriculture to low-productivity services and construction, rather than to manufacturing. As a result, agriculture still accounts for more than 40 per cent of total employment, leading to persistently low labour productivity and many workers experiencing low and unstable incomes.

Time of Reclaiming Decent Work in India

The ILO World of Work Trends 2026 warns that stable unemployment figures do not necessarily indicate progress toward decent work. India's labour market reflects this warning. Informality, working poverty, youth exclusion, gender inequality, and technological change continue to shape the realities of many workers.

Tackling these challenges requires more than economic growth alone. As the ILO points out, coordinated efforts by governments, employers, and workers are crucial to strengthening labour institutions. They also need to expand social protection, regulate new forms of work, and put social justice at the heart of development strategies.

For India, reclaiming decent work is both an economic need and a social obligation. This means breaking down deep-rooted caste and gender barriers. It also involves effectively applying the four labour codes to ensure real worker protection.

Furthermore, there needs to be a shift from symbolic dignity to actual agency, enabling workers to move from insecure, exploitative jobs to safer, more productive, and more respected employment. A development approach that focuses on workers' well-being rather than prioritising growth at any cost is essential to ensuring that economic progress leads to better lives for working people.