A. J. Philip

A. J. Philip

.jpeg)

I often receive suggestions from my readers about the subjects I should take up in my weekly column in this journal. Some are gently persuasive, some angry, some merely curious. Occasionally, one of them sends me a document and asks a simple question: Can this really be done in a constitutional democracy?

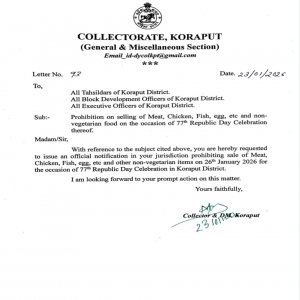

That was the case when a friend from Thiruvananthapuram forwarded to me a copy of an official order issued by the Collector and District Magistrate of Koraput, Odisha, on January 23. I found out his name was Manoj Satyawan Mahajan.

The order instructed all his subordinate officers to prohibit the sale of "meat, chicken, fish, egg etc and non-vegetarian food on the occasion of the 77th Republic Day celebration." I read it twice, partly in disbelief and partly in amusement.

Republic Day, of all occasions, was being invoked to justify an intrusion into what people eat. I wondered under what authority the Collector thought he could issue such a directive, one that ran directly counter to the freedom of choice that the Constitution guarantees under Article 21.

The Supreme Court had been unambiguous on this matter. What one eats is part of one's personal liberty and privacy. Non-vegetarians cannot be compelled to become vegetarians, whether by social pressure or executive fiat. Food habits are not merely matters of taste; they are shaped by geography, culture, livelihood and history. To interfere with them is to interfere with dignity itself.

What made the Koraput order even more startling was the social composition of the district. Koraput is a region where Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes constitute a majority of the population. They are, by and large, non-vegetarians. Meat, fish and forest produce are not luxuries for them but staples. From the caste name of the Collector, I presume he is a vegetarian. There is nothing wrong with that. The problem begins when personal belief is elevated into administrative morality and imposed on others in the name of nationalism.

Man, after all, is one of the few animals that are both carnivore and herbivore. An elephant will die rather than eat meat; a lion will die rather than eat leaves. Humans alone have evolved with the ability—and the freedom—to eat both. To deny that freedom is to deny a basic fact of human existence.

Had this Collector been born in the Northeast, he would probably have been served the best piece of mutton, beef or fish at official dinners. Had he been born in China, he might have eaten everything that moves, as the stereotype goes. Had he been born in a village in Koraput itself, there is every chance he would have relished non-vegetarian food without guilt or ideology.

I know a little about Koraput, not from tourist brochures but from history. It was a region that Emperor Ashoka could not occupy during the Kalinga war. Ashoka's own edicts suggest how he later tried to wean the people of Koraput into becoming his subjects, aware that conquest by force had failed. Culture, not coercion, was his belated lesson.

I am an unashamed lover of district gazetteers. These were written originally by British officers serving as District Magistrates or Collectors. Whatever their colonial limitations, the gazetteers are extraordinary documents. They describe the geography of a district, the people who lived there, their dress, their food habits, their flora and fauna. They are mines of information, written by administrators who actually took the trouble to know their districts.

Gazetteer-writing has long since come to an end. Today's Collectors are too busy dancing to the tunes of politicians, currying favour for better and more lucrative postings. When the obsession is with the next transfer or plum assignment, who has the time to study the district, to understand how people live and what they eat?

Koraput had the good fortune of having a district gazetteer prepared by RCS Bell, ICS. Before the district came into being in 1936, it was part of the Visakhapatnam district. Bell relied heavily on the Vizagapatam Gazetteer prepared by W Francis, ICS, published in 1907, and DF Carmichael's Manual of the Vizagapatam District published as early as 1869.

After Independence, a new District Gazetteer, based largely on these earlier works, was edited by Nilamani Senapati, ICS, and published in 1966. Let me quote a few lines from this document, which every Collector posted to Koraput should be required to read before assuming charge:

"The basis of their food is rice, millet and pulses. They have no idea of frying. Their great love is for meat. This they usually boil with rice or millet. Crabs are boiled or roasted between leaves. Fish are boiled. Roots are boiled separately. Bamboo shoots are very popular. Field rats are roasted on a skewer. Red ants are tied up with mushrooms in a leaf bundle, which is put in embers to roast."

I wish the Collector had read even this one paragraph of the gazetteer. Had he done so, he would not have dared to issue an order banning non-vegetarian food, even for a day.

There was, of course, a strong protest, forcing him to withdraw the order. But the damage was already done. The mindset had been exposed. The Collector seemed to believe that the "sanctity" of Republic Day would be spoiled if there was the smell of non-vegetarian food—something like a bull's-eye egg or a chicken samosa—in the air.

Mahajan, perhaps, did not know that the chief guests at India's 77th Republic Day parade in New Delhi were European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and European Council President António Costa. For all one knows, they might well have eaten for breakfast the very foods he despises—sausages, ham, scrambled eggs—rather than boiled putta (baby corn), which the poor in Odisha eat.

I once stayed with the late Archbishop Raphael Cheenath in Bhubaneswar. I saw him eating boiled corn for breakfast. Sensing my discomfort, he smiled and said, "Don't worry, you will get the breakfast of your choice, even if it is bread, toast and omelette." That, to me, is inclusivity: accommodating difference without imposing sameness.

Contrast this with exclusivity masquerading as principle. When Narendra Modi first visited the United States as Prime Minister, President Barack Obama hosted a state dinner that was essentially vegetarian to respect his food preferences. Yet, on the pretext of some ritual, Modi reportedly had only a glass of water. That is not inclusivity; that is drawing a line even when accommodation is offered.

At the heart of Mahajan's circular lie two deeply flawed assumptions that have long poisoned India's public discourse on food: first, that vegetarian food is inherently holier than non-vegetarian food; and second, that those who eat vegetarian food are morally or culturally superior to those who do not. These notions are not only historically untenable but also socially dangerous. They turn something as intimate and necessary as food into a marker of hierarchy, exclusion and, ultimately, state control.

I was reminded of this mindset many decades ago when a distraught mother came to me with a request. She wanted publicity for an exhibition of paintings done by her deceased son. As she spoke of his talent, kindness and sensitivity, she suddenly added, almost as an afterthought but clearly as a badge of honour: "He was so good that he did not even eat non-vegetarian food."

I understood her grief and did not wish to wound her feelings, but I gently pointed out that eating non-vegetarian food did not make anyone less good or less human. That reflexive association of virtue with vegetarianism has been drilled into our collective consciousness over generations, and today it is being weaponised by the state.

Food bans are not new in India, but their moral justification has grown more aggressive in recent years. Long before the BJP came to power, non-vegetarian food was prohibited in Kurukshetra, the land where the Mahabharata war was fought and where, by any reckoning, thousands fell to arrows, swords and maces.

The irony of banning meat in a place sanctified by mass slaughter seems to escape the moral custodians. Unfortunately, this logic has since travelled far beyond Kurukshetra, extending to places like Haridwar and even along routes taken by Kanwarias, where the state assumes the right to regulate what everyone else may eat.

Recently, a town in Gujarat was declared the world's first "vegetarian city" because it houses a cluster of Jain temples. Jains, as is well known, do not eat onions or root vegetables. If religious sentiment were to be taken to its logical conclusion, the ban should have been extended to potatoes, yams and carrots as well. But bans are never about logic; they are about power and symbolism. They signal who belongs and who must adjust, who is pure and who is suspect.

Kerala offers a striking counterpoint. When famine and poverty stalked the land, it was Christian missionaries who introduced tapioca as a cheap and filling food to stave off hunger. Food here was about survival, not sanctimony. I recently read that a Mar Thoma bishop introduced what later became Kerala's most popular banana variety, brought from a town in Tamil Nadu.

These interventions were not about religious purity; they were about feeding people. In traditional Kerala society, even food carried a caste label. Upper castes ate rice; the poor survived on millets, roots and jackfruit. Dosa, idli and coconut chutney were privileged foods of Brahmins, while puttu and kadala curry were associated with lower castes. To pretend that vegetarianism is an ancient, universal Indian value is to erase these lived histories.

Serious scholarship demolishes the myth even more decisively. The late historian Dwijendra Narayan Jha, in his meticulously researched The Myth of the Holy Cow, cited textual evidence to show that beef was consumed in ancient India, including during the Vedic period. The cow's absolute sanctity, he argued, is a later social and political construction.

Evolutionary theory, too, tells us that early humans were hunters; non-vegetarianism preceded agriculture. Even today, a large majority of Indians eat meat or fish. Scheduled Tribes, Scheduled Castes, Muslims, Christians and most OBC communities are non-vegetarian. Are we to believe that all of them are morally inferior?

Regional practices further expose the hollowness of food-based moralism. In West Bengal, many Brahmins cheerfully describe fish as a "vegetable" and relish it without guilt. In Bihar, few cook fish and mutton better than Maithil Brahmins. Swami Vivekananda, now selectively appropriated as a Hindu icon, was himself a non-vegetarian. Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the BJP's own tallest leader, loved trout from Himachal Pradesh and, by several accounts, found it hard to resist chicken kebabs at social gatherings. If food defined virtue, where would these icons stand?

The hypocrisy becomes cruel when bans destroy livelihoods. In the Nuh district of Haryana, an overzealous police officer once banned the sale of biryani on bicycles, citing hygiene. Muslim men would balance large vessels on carriers and sell affordable portions to daily-wage earners. Thousands lost their livelihoods overnight.

Not a single case of illness had been reported from this practice. Contrast this with Indore, celebrated as India's cleanest city, where hundreds fell ill, and some died when drinking water lines mixed with sewage. No official was punished. Hygiene was merely a pretext; prejudice was the real motive.

The same pattern is visible in Uttar Pradesh, where meat and fish sales are routinely banned during religious festivals without a thought for butchers and vendors. Who compensates them for lost income? One of Yogi Adityanath's first symbolic acts was to remove all leather goods from his office and residence, as though leather itself were impure. The leather industry, employing large numbers of Scheduled Castes and Muslims, has suffered immensely. The beneficiaries are corporate manufacturers of artificial leather, not the poor.

Earlier, farmers in North India could sell unproductive cattle to butchers. Today, with slaughter effectively criminalised, these animals are abandoned on roads, eating plastic and destroying crops. Modi happily poses with healthy cows and calves for photographs, but shows little concern for the suffering animals roaming Delhi's streets or ravaging farmers' fields.

The principle is simple and should be non-negotiable in a democracy: someone's food may be someone else's poison, but neither the state nor self-appointed Mahajans has any right to decide what citizens may eat. Food is culture, livelihood and personal choice. When governments police plates, they are not protecting faith; they are eroding freedom.