.jpg)

Subhas Chandra Bose was a leader of the younger, radical wing of the Indian National Congress. He was elected President of the Congress at its Haripura Session in 1938 and re-elected in 1939, this time defeating Gandhi's nominee Pattabi Sitaramayya in a bitterly fought election.

He wanted the Congress to be organised on the broadest anti-imperialist front against the British with the objective of winning freedom. And "he didn't approve of any step being taken by the Congress, which was anti-Japanese or anti-German or anti-Italian."

There was a big difference in outlook between him and others in the Congress Working Committee, both on foreign and national issues, which led to a break. In August 1939, he publicly attacked the Congress policy, forcing the latter to take disciplinary action by banning him from holding any elected office in the Congress for three years, leading to his resignation.

The Congress laid down a dual policy regarding the Second World War. On the one hand, it opposed fascism, nazism and Japanese militarism, and, on the other, was willing to join any attempt to stop the aggression and invasion, emphasising the freedom of India.

Without freedom, the war would be like any old war-a contest between rival imperialism and an attempt to defend and perpetuate the British Empire. It, therefore, demanded that India should not be committed to any war without the consent of her people or their representatives, and that no Indian troops be sent for service abroad without such consent. It is absurd to raise the banner of democracy elsewhere by denying it to India.

The Second World War began on September 1, 1939, with the invasion of Poland by Germany and the subsequent declaration of war on Germany by France and the United Kingdom. The British Government, fighting the war with the Allied Nations, had dispatched more than two and a half million Indian soldiers to fight against the Axis Powers.

The Indian troops had been used as mercenaries in Singapore, Burma, China, Iran, the Middle East and Africa, causing embarrassment to India, with other countries mocking her: "You have not only lost your own freedom but you help the British to enslave others."

When war was declared in Europe, the Viceroy Lord Linlithgow announced that India was also at war. Thus, "one man, and he a foreigner and a representative of a hated system, could plunge, four hundred millions of human beings into war without the slightest reference to them."

This outraged the Congress, which had been spearheading the freedom movement in India. On September 14, 1939, the Congress issued a statement: "a free democratic India will gladly associate herself with other free nations for mutual defense against aggression..." and asked the British Government "to declare in unequivocal terms what their war aims are in regard to democracy and imperialism and the new order that is envisaged... Do they include elimination of imperialism and the treatment of India as a free nation…"

Since the British didn't respond, the Congress governments in the Provinces (eight out of eleven) were asked to resign in protest. The legislatures were not dissolved; instead, the governors assumed all the powers of the provincial governments, with no accountability.

The Congress, at its session held in Ramgarh, Bihar, in March 1940, under the presidency of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, decided that civil disobedience was the only course left. But it was given up due to Germany's blitzkrieg over England, when its very existence itself was at stake.

Another attempt was made to arrive at a settlement with the British Government. It asked for recognition of Indian freedom and the establishment of a national government at the Centre to cooperate in the war efforts and identify with the struggle against fascism and nazism.

Winston Churchill, the British War Prime Minister, was unwilling to concede. He stood out as an uncompromising opponent of Indian freedom. In 1930, he had said: "Sooner or later you will have to crush Gandhi and the Indian Congress and all they stand for... We have no intention of casting away that most truly bright and precious jewel in the crown of the King... which constitutes the glory and strength of the British empire."

The freedom movement now entered the last phase. Gandhiji's lifelong non-violent struggle for India's freedom was at stake. How far would the non-violent technique succeed against naked aggression and invasion?

With the rapid advance of the Japanese in Burma and the fall of Rangoon on March 8, 1942, the war entered the Indian frontiers. Sir Stafford Cripps Mission failed to resolve the deadlock. To Gandhiji, as Nehru described, "inaction at that critical stage and submission to all that was happening had become intolerable... Submission meant that India would be broken in spirit and her people would act in a servile way and their freedom would not be achieved for a long time... It would mean the complete demoralisation of our people and their losing all the strength that they had built up during a quarter of a century's unceasing struggle for freedom."

He saw it as an opportunity to convert the sullen passivity of the people into a spirit of non-submission and resistance, an outlet for action to release pent-up passion and energy.

The Congress Working Committee met at Wardha on July 14, 1942. It passed a resolution demanding complete independence from the British Government and issued an ultimatum to launch massive civil disobedience if the British did not accede to the demand.

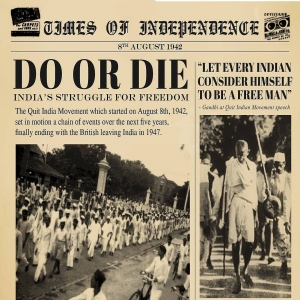

Surprisingly, a national leader, C. Rajagopalachari, had quit the Congress in protest against the decision. Soon, the Congress held the historic session in Bombay, at Gowalia Tank Maidan (now August Kranti Maidan), on August 7 and 8, 1942.

It passed a Resolution, which came to be known as the 'Quit India Resolution.' The Resolution was drafted by Pandit Nehru. He moved the Resolution, seconded by Sardar Patel, which was passed with a majority.

The Resolution called for immediate recognition of Indian freedom and the ending of the British rule in India as "the continuation of that rule is degrading and enfeebling India and making her progressively less capable of defending herself and of contributing to the cause of world freedom."

Gandhiji addressed the people, exhorting them to act: "Here is a mantra, a short one that I give you. You may imprint it on your hearts and let every breath of yours give ex

The next morning, August 9, all the Congress leaders were arrested and imprisoned in Ahmednagar Fort, and Gandhiji in Aga Khan Palace, Poona.

At a time when India was stirred by the fight for her freedom, honour, and dignity, some elements found it convenient to collaborate with the British. The Muslim League, the Hindu Mahasabha, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and the Indian States opposed the Quit India movement.

Hindu Mahasabha President VD Savarkar, in a letter titled 'Stick to Your Posts,' instructed the Hindu Mahasabhaites, who were "members of municipalities, local bodies, legislatures or those serving in the army... to stick to their posts", and not to join the Quit India Movement.

And Syama Prasad Mukherjee, the leader of Hindu Mahasabha in Bengal- a partner in the ruling coalition led by Fazlul Haq-wrote a letter dated July 26, 1942 to Sir John Herbert, Governor of Bengal, advising him how to respond, if the Congress gave a call to the British rulers to quit India, and assuring him that the Fazlul Haq Government, along with its alliance partner the Hindu Mahasabha, would make every possible effort to defeat the Quit India Movement.

According to the historian RC Majumdar, he "expressed the apprehension that the movement would create internal disorder and will endanger internal security during the war by exciting popular feeling and... that any government in power has to suppress it..."

The Quit India campaign was ruthlessly crushed by the British Government, swiftly responding with mass detentions. Over 100,000 arrests were made, mass fines were levied, and demonstrators were subjected to public flogging.

By early 1944, India was mostly peaceful, while the Congress leadership was still incarcerated. A sense that the movement had failed depressed many nationalists, while Jinnah and the Muslim League, the RSS, and the Hindu Mahasabha sought to gain political mileage by castigating Gandhi and the Congress.