Fr. Gaurav Nair

Fr. Gaurav Nair

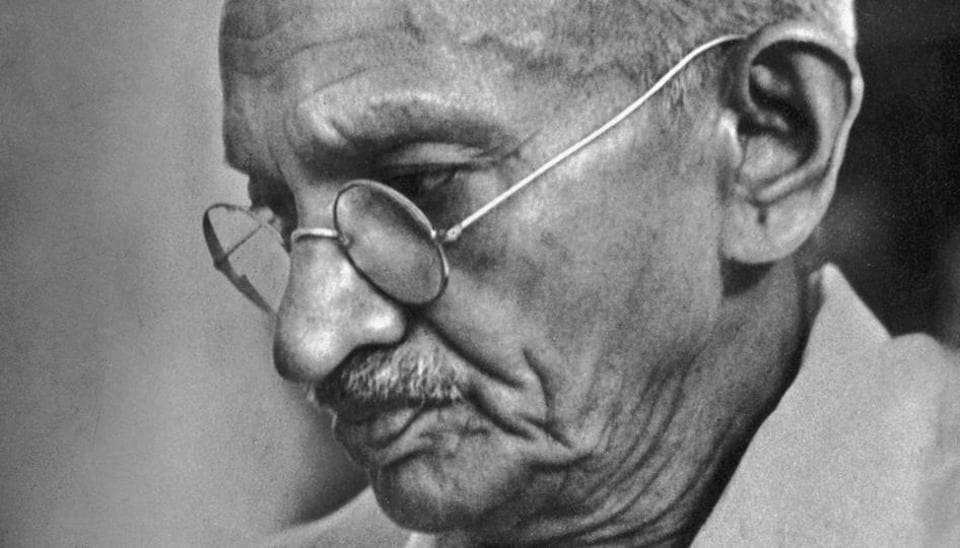

January 30 marks the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi. Martyrs' Day stands apart in India's public calendar. It carries the quintessence of grief, warning, and responsibility. To most of our citizens, it does not carry any meaning; many may not even be aware of such a practice. Yet, the silence observed at 11 am each year does more than honour sacrifice. Since the ascent of the Saffron ideology to the nation's highest chair, it symbolises the pause before power rewrites memory.

Gandhi's killing was a political murder. It emerged from an ideology that rejected pluralism, distrusted constitutionalism, and viewed violence as a form of correction. Remembering this truth remains the core purpose of Martyrs' Day.

In recent years, this clarity has been under strain. Hindutva groups have worked steadily to blur the moral lines of 1948. Nathuram Godse appears in speeches, plays, social media posts, and commemorations. Sometimes he is praised openly. At other times, he is excused, relativised, or separated from the politics that shaped him. Gandhi, meanwhile, is reduced to a harmless symbol, expropriated of his ethical challenge.

Martyrs' Day resists this drift. It restores sequence and responsibility. Gandhi stood for non-violence, religious coexistence, and constitutional morality. Godse rejected all three. The shot fired on Birla House grounds targeted an idea of India that refused majoritarian rule.

Historical revisionism thrives on confusion. Hindutva narratives have consistently attempted to recast Gandhi as weak, indulgent, or anti-Hindu, whereas Godse is framed as a patriot pushed to extremes. These claims echo the language Godse himself used at his trial. The continuity between past and present rhetoric cannot be discounted.

The BJP's public stance still appears to be very cautious. National leaders still pay tribute at Rajghat. Official statements praise Gandhi's sacrifice. However, parallelly, party affiliates and ideological allies have continued to amplify messages that undermine his legacy. This duality has normalised denial without formal endorsement.

Martyrs' Day must become an interrupt to this arrangement. It insists on context. The rituals of remembrance emerged through collective political choice after independence. Nehru's insistence on nationwide silence reflected a belief that memory required discipline. Public mourning was meant to anchor democratic values in daily life.

That intent matters today. Attacks on minorities, calls for cultural, linguistic, and caste dominance, and suspicion of dissent have grown louder. Gandhi's vision stood against each of these tendencies. His death revealed how fragile moral consensus can be when fear is mobilised.

Commemoration does not demand uncritical reverence. Gandhi's ideas may invite debate; his limits may deserve scrutiny. Martyrs' Day does not block disagreement; it blocks erasure and refuses to allow hatred to pose as patriotism.

Our republic survives through a shared remembrance. Forgetting the meaning of January 30 risks forgetting why the Constitution exists at all. The silence observed that morning measures distance from violence, not reverence for power.

Martyrs' Day still remains a checkpoint - against distortion - against denial - against the steady narrowing of India's moral horizon.