.jpg) Aakash

Aakash

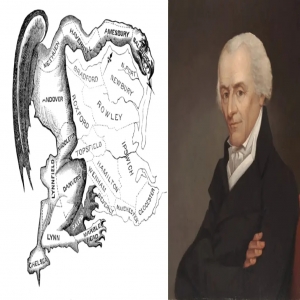

In 1812, Governor Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts signed a law redrawing state senate districts to favour his party. One district coiled so grotesquely around opposition strongholds that a critic likened it to a salamander. Thus, "gerrymandering" was born. Over two centuries later, the art of shaping electoral boundaries remains controversial.

Delimitation, the process of demarcating political constituencies, is not just a technical exercise. It is a mirror reflecting struggles to balance representation, power, and identity. Nowhere is this tension more palpable than in India, where after years of trying to avoid properly defining or delimitating political constituencies, it has become a Gordian knot entangled in a very real existential fear of marginalisation.

Delimitation's origins are as old as representative democracy itself. Ancient Athens used a lottery system to assign political power and avoid territorial bias. But, modern delimitation emerged alongside nation-states and mass enfranchisement. The 19th-century British Reform Acts sought to dismantle "rotten boroughs"—electoral districts with tiny populations controlled by aristocrats—while expanding representation for industrial cities like Manchester. Yet, the core dilemma persisted: How can the population be translated into a political voice without diluting it?

The 1787 Constitution's "Great Compromise" in the US balanced state equality in the Senate with population-based House seats. But by 1812, gerrymandering had already weaponised mapmaking. The 1965 Voting Rights Act later targeted racial gerrymandering, forcing Southern states to end discriminatory redistricting. Today, advanced algorithms allow precision gerrymandering, turning what was once a crude art into a science.

Globally, approaches vary. The UK employs independent Boundary Commissions, insulated from politics, to report on seat adjustments every eight years. Canada's non-partisan commissions prioritise "communities of interest" over rigid population parity. Australia's redistricting, overseen by electoral commissions, emphasises geographic contiguity and voter convenience. Contrast this with Kenya, where delimitation has sparked ethnic violence, or Iraq, where sectarian quotas dictate seat allocations. Each system reveals a trade-off: mathematical fairness versus cultural cohesion and efficiency versus inclusivity.

India's tryst with delimitation is uniquely fraught. The Constitution initially mandated readjustment after every census to reflect population changes. Between 1952 and 1973, three Delimitation Commissions redrew boundaries, aiming for "one person, one vote." However, in 1976, during the Emergency, the 42nd Amendment froze seat allocation in Parliament and state assemblies until 2001—a move ostensibly to discourage penalising better population control. The freeze was later extended to 2026, leaving India's electoral map anchored to 1971 population data.

This freeze has created staggering asymmetries. By 2023, a Lok Sabha seat in Tamil Nadu represents 18 lakh people, while one in Bihar represents 28 lakh. Southern states, which curbed population growth, now fear losing political clout to northern states with unchecked populations. The 2002 Delimitation Commission, tasked with updating boundaries within the frozen seat cap, ignited fresh tensions. Its recommendations—implemented in 2008—reshuffled constituencies to align with 2001 demographics but left north-eastern states in limbo due to ethnic unrest. Reserved seats for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) also faced upheaval as population shifts triggered demands for reclassification.

States like Kerala and Tamil Nadu argue they are penalised for successful family planning, while Uttar Pradesh and Bihar gain disproportionate influence. The freeze, intended as a temporary incentive, has morphed into a permanent crisis.

Other democracies have sufficient cautionary tales to offer. In the US, partisan gerrymandering has birthed "safe seats," where incumbents face no real competition. In 2019, Wisconsin's legislative maps—drawn by Republicans—awarded them 63% of seats with 46% of the vote. Conversely, Chile's 2017 redistricting erased authoritarian-era biases, boosting underrepresented urban voters. South Africa's post-apartheid delimitation prioritises racial redress, yet critics argue it entrenches ethnic voting patterns.

Technology's role is double-edged. GIS mapping and AI enable granular analysis but also micro-targeting. In 2018, Pakistan's Election Commission used digital tools to eradicate overlapping constituencies, yet allegations of bias persisted. The paradox is evident: the more precise delimitation becomes, the more susceptible it is to manipulation. However, that is almost impossible in India, which is home to far more cultures and unwieldy and organic population distributions.

At its core, delimitation is a zero-sum game. For every winner, there is a loser. In India, three fault lines deepen the deadlock:

1. Smaller states fear being overshadowed; populous states demand their numeric due. The southern backlash against the 15th Finance Commission—which used 2011 population data—hints at the uproar a delimitation exercise could unleash.

2. Reserved seats for SCs/STs, while constitutionally mandated, often clash with shifting demographics. The rise of OBCs (Other Backward Classes) has fueled demands for sub-categorisation, further complicating boundary-making.

3. Rewarding states for unchecked growth undermines family planning. Yet ignoring demographic reality distorts representation.

Similar tensions simmer internationally. Belgium's linguistic divides and Nigeria's north-south rivalry show how delimitation can inflame sectarian tensions. Even technocratic solutions falter: Mexico's independent redistricting institute, lauded as a model, still faces accusations of urban bias.

India's 2026 deadline looms like a sword overhead. Proposals to cap northern seats or add new ones for the south risk constitutional challenges. A "weighted voting" system—where MPs from smaller states get more votes per capita—has been dismissed as impractical. Some suggest delinking Lok Sabha seats entirely from the population instead of using a mix of criteria like area, literacy, and revenue. But a consensus is not yet visible on the horizon.

Globally, the push for independent commissions gains momentum, though their efficacy depends on political buy-in. Ireland's citizen assemblies and Iceland's crowdsourced redistricting experiments offer innovative, if untested, models.

Delimitation, ultimately, is democracy's self-correction mechanism—a reminder that governance must evolve with the governed. Yet, as India's impasse shows, evolution is never seamless. In the words of political scientist David Butler, "Boundary changes are where the silent arithmetic of the census meets the noisy algebra of politics." The numbers may be neutral, but their interpretation never is.

As India grapples with its frozen map and the world watches its own redistricting battles, one truth endures: Delimitation is not a problem to be solved but a process to be managed—a perpetual negotiation between the ideal of equality and the reality of human ambition. The maze has no exit, but perhaps the struggle to navigate it keeps democracy alive.