.jpg) Aakash

Aakash

Each election, the air in Indian cities and villages hangs thick with the acrid scent of political ambition. Local candidates' voices, amplified by crackling loudspeakers, sliced through the smog and dust: "Remember who you are! Remember your blood, your community, your faith!

Every single day, Dalit labourers shift their weight, eyes hollowed by generations of inherited exhaustion as they await daily work. Youngsters scroll through their phones, algorithms feeding them videos amplifying their perceived religion or caste-based grievances.

In cities, entrepreneurs lament the 'unnecessary divisions' holding back the economy, sipping single-origin coffee in a high-rise tended by silent workers from another state, speaking another tongue. This is India in 2025: a nation of a billion-plus souls.

Despite decades of constitutional equality and economic aspiration, caste remains the bedrock upon which India's social and political edifice precariously rests. It's not merely tradition; it's a meticulously calculated electoral algorithm which is being kept alive by those in power.

Political parties deploy caste demographics with the precision of military strategists, fielding Yadav candidates in Bihar, Dalit leaders in Punjab, and Maratha-centric alliances in Maharashtra. All these are designed to harvest the votes of tightly bound communities. According to surveys, over 70% of voters still prioritise caste loyalty over governance records or policy platforms.

This isn't a myth; it's the engine of power. The fierce, ongoing battle over the national caste census lays this bare. Supporters argue decades of ignoring caste have meant "flying blind, designing policies in the dark while claiming to pursue social justice." They view data as a weapon against systemic disadvantage, a means to allocate resources towards those historically marginalised and oppressed.

Opponents, however, recoil. They fear legitimising a system India should transcend, warning it will harden divisions, ignite demands for unaffordable quotas, and unleash social unrest. For the ruling BJP, which was historically resistant to caste enumeration in favour of a unified Hindu identity, the recent U-turn to embrace the census is purely an admission of pragmatism over ideology. It is a recognition that caste's gravitational pull is stronger than any nationalist narrative.

A caste census is an audit of power within the supposed unity of Hindu society. It will threaten the illusion of homogeneity carefully cultivated by Hindu nationalist politics, but in the end, it may work out in their favour.

If caste is the bedrock, communalism is a volatile fault line constantly in threat of being ruptured. Communalism transforms places of worship into battlegrounds and neighbours into threats. Today, it manifests in terrifyingly modern ways: viral hate speech on WhatsApp, orchestrated mob lynchings over allegations of cow slaughter, the ghettoisation of minorities, and riots that erupt with frightening predictability.

The saffron gang is known to fuel the fire of division. They wield religious identity as a blunt instrument for vote-bank politics. The diatribe fosters an "us versus them" mentality, where one community's gain is seen as another's loss. This eventually breeds deep suspicion and mutual antagonism. This fragmentation isn't just about Hindus and Muslims; it seeps into intra-faith dynamics and impacts Christians, Sikhs, and others.

While not currently at its fever pitch like caste or religion, linguistic pride remains potent. Demands for linguistic states shaped modern India's map. Today, there are anxieties about Hindi imposition that spark fierce resistance in southern and eastern states. It is considered not only protecting the language but also distinct cultural identities and political autonomy.

Economic liberalisation birthed a glittering elite and a burgeoning middle class but has also left behind hundreds of millions outside its ambit. The billionaires and the landless Dalit labourers inhabit worlds with little common ground that is vanishing even now. This economic apartheid has fueled resentment and disillusionment and enabled the incursion of hatred.

Policies like reservations (affirmative action) have become flashpoints, with privileged castes decrying "reverse discrimination" when quotas are discussed or expanded.

Indigenous communities face a unique double fragmentation. They strive to preserve distinct cultural identities and rights over ancestral lands against the onslaught of assimilation and displacement driven by resource extraction and development projects. Their struggle is against both the mainstream and within, against forces that do not care about the Adivasis' life or death but their own profits.

The rise of polarising majoritarian nationalism has triggered a fierce counter-mobilisation of liberal, secular, and social justice ideologies. Social media has become an accelerant, creating impenetrable echo chambers. Debates around history, nationalism, citizenship, and even scientific temper have become bitterly divisive, turning comment sections into minefields.

The debate over a national caste census captures India's anxiety over its fragmentation. It's far more than a statistical exercise; it's a referendum on what kind of nation India wants to be. Proponents view it as the essential first step towards true social justice – a means to move beyond outdated quotas and target resources and representation accurately. As Bihar's survey revealed that OBCs and EBCs form over 63% of its population, demands instantly surged to raise reservation quotas beyond the current 50% cap.

Opponents, including many from historically dominant castes, view it with dread. They see it as a Pandora's box that will deepen the already persistent divisions. This will fuel endless demands for quotas, paralyse governance, and ultimately, balkanise the society.

India's multifarious fragmentations are not new. Its history is one of astonishing diversity held in a dynamic, often tense, equilibrium. Yet, the intensification of these divides in 2025 feels different. The scale, the speed amplified by technology, the weaponisation of identity by political entrepreneurs, and the sheer exhaustion of constant communal and caste calculations weigh heavily.

The promise of modernity, that education, urbanisation, and economic growth would dissolve these antique bonds remains largely unfulfilled. If anything, prosperity often seems to sharpen the lines, creating fortified enclaves of privilege while leaving others further behind.

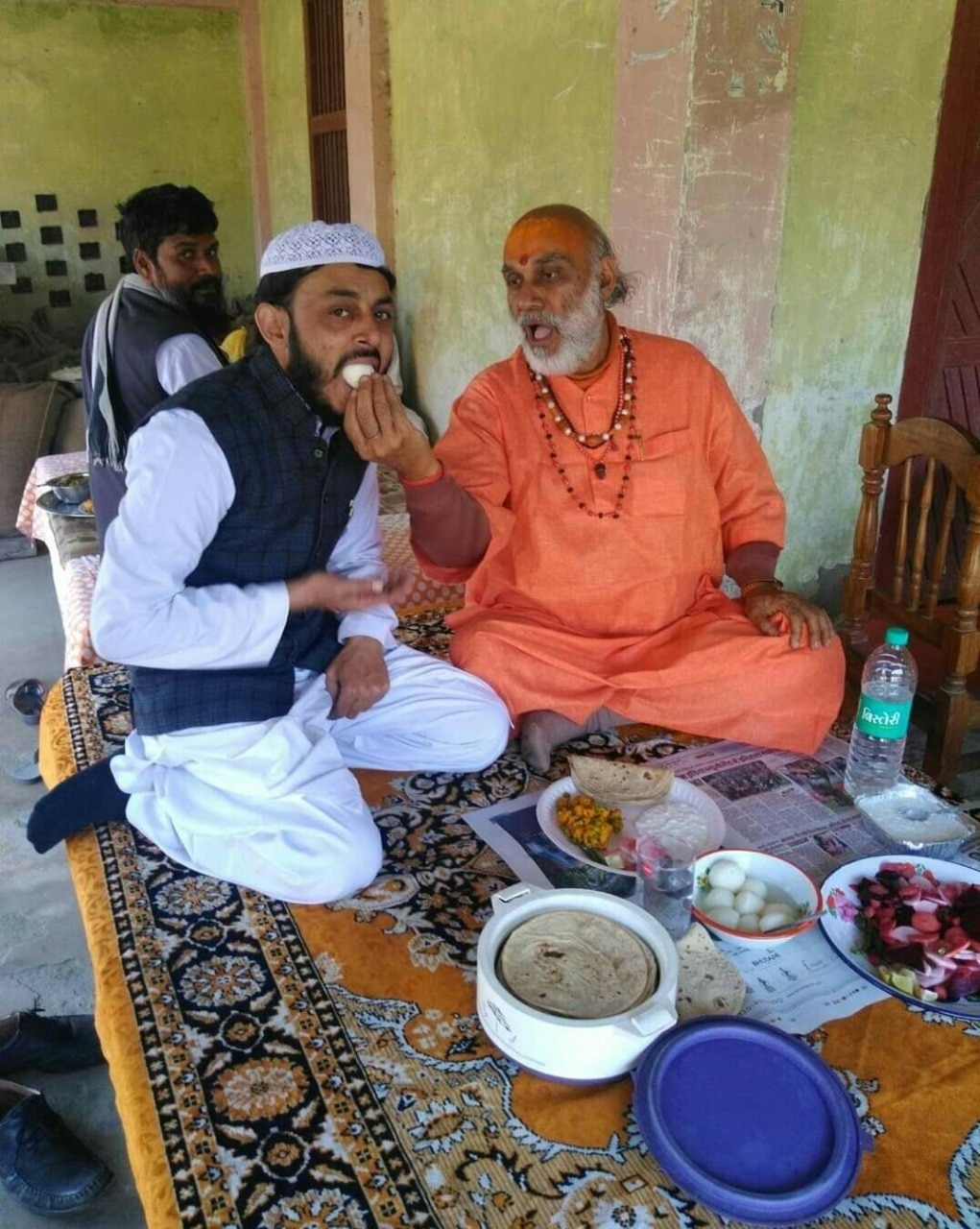

Is India doomed to splinter under the weight of its own diversity? Not necessarily. The very act of debating the caste census, however painfully, signifies a skirmish with these inequalities rather than a blanket denial. There are still spaces in marketplaces, in moments of crisis, in the quiet defiance of ordinary people rejecting hate where our ideals transcend our identity.

The resilience of India's democratic framework, however strained, still provides a space for negotiation and protest, which is absent in many places. The challenge, though monumental in its scope, is to forge a national identity that is both strong and flexible enough to acknowledge, respect, and celebrate these deep diversities.

We need to move beyond politics solely defined by who we are, our caste, religion, or language towards one that addresses what we need: dignity, opportunities, and justice.