A. J. Philip

A. J. Philip

.jpg)

It was the Hindustan Times' chief photographer, the late Arun Jetlie, who taught me how to drive in the mid-eighties. He would come home, take me in the car, and drive to the Raj Bhavan area in Patna, where the roads were wide and welcoming. Calm and methodical, Arun was such a natural teacher that I often felt he could have run a driving school and made it a success.

Another lesson came years later, and it had nothing to do with driving. It came from Narendra Modi, then Chief Minister of Gujarat. The word he taught me was "Miya." Though I had been living in North India since 1973—moving through newsrooms, railway stations, court corridors, and political meetings—I had never heard the word used the way Modi did.

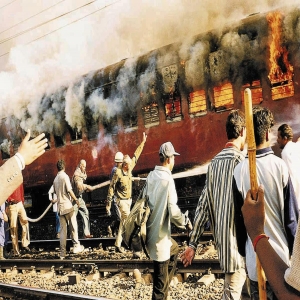

The setting was the horrific violence that followed the burning of two compartments of the Sabarmati Express at Godhra on February 27, 2002, in which 59 karsevaks returning from Ayodhya were killed. What followed does not need recounting. Gujarat burned, and the moral collapse of the state apparatus was laid bare. Modi wanted elections immediately, riding the polarisation that followed the violence.

When I visited Godhra during that period, one question kept troubling me. Why was there no reaction in neighbouring Madhya Pradesh, just a few kilometres away, while riots broke out hundreds of kilometres away in Ahmedabad and other parts of Gujarat? Violence, it appeared, was not spontaneous. It travelled with purpose.

Modi exerted enormous pressure on the then Chief Election Commissioner, James Michael Lyngdoh, to hold elections without delay. He refused, arguing that a minimum level of normalcy was a prerequisite for free and fair elections. That refusal provoked Modi into publicly abusing him at rallies. He would pronounce Lyngdoh's full name with deliberate emphasis and make wild allegations—that he took instructions from Sonia Gandhi, whom he supposedly met every Sunday at the Cathedral Church in New Delhi.

The allegation was absurd, and Modi knew it. Sonia Gandhi is a Hindu by virtue of marrying a Hindu. Lyngdoh is an atheist who never went to any religious place for worship. Facts, however, were beside the point. The insinuation was what mattered.

When elections were eventually held, Modi campaigned against what he called "Miya Musharraf," as though Pakistan's then-President, General Pervez Musharraf, was contesting the Gujarat Assembly elections. It was during this campaign that I first heard the word "Miya" being used openly and repeatedly as a term of abuse for Muslims.

Ironically, the word itself is not abusive. "Miya" is a Persian-Urdu honorific—roughly equivalent to "sir" or "gentleman." In many parts of South Asia, it is still used neutrally and sometimes even respectfully. Words are not born as slurs; they are turned into slurs by politics, repetition and intent.

Language has always intrigued me, especially the strange and often unsettling journeys abusive words take. In much of the Western world, the name of Jesus is routinely used as a swear word—uttered in anger, frustration or disbelief, stripped of reverence and reduced to an expletive. Few pause to consider how a name central to faith and worship became a verbal reflex for irritation.

The word "Miya" resurfaced in public discourse recently, this time in Assam, from Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma. Addressing his party colleagues, Sarma offered them tips on how to deal with "Miyas." A Special Intensive Revision of the electoral rolls is currently underway in Assam, and he urged his cadres to file objections against "Miyas" whose names appear in the voters' list.

Sarma went on to tell his cadres that it was their bounden duty to harass "Miyas" so thoroughly that they would be forced to leave Assam. He even offered practical advice. If a rickshaw-puller is to be paid ?5, give him only ?4 if he is a "Miya." It is difficult to recall another Chief Minister who has descended to such transactional cruelty. He effectively authorised his supporters to harass a community in every possible way, to push them to the wall so that they would leave the state—and perhaps the country.

When people like Harsh Mander, who served as an IAS officer in Gujarat and understands where such rhetoric leads, filed criminal cases against Sarma, the Chief Minister clarified that he used the term "Miya" only to refer to "infiltrators." Let us, for the sake of argument, assume that this explanation is truthful.

It is now twelve years since Narendra Modi became Prime Minister and Amit Shah became Home Minister. India's borders are guarded by the Border Security Force and the Indian Army. How then does large-scale infiltration take place without their knowledge? If infiltrators are indeed settling down in Assam, it reflects a monumental failure of the Central government to secure the borders. That failure cannot be blamed on a cycle-rickshaw puller.

When India became independent, almost all the white people left for Britain, selling their properties at throwaway prices. One such property—the finest hotel in Shimla—was bought by MS Oberoi, who worked there. Today, Oberoi Hotels across the world symbolise elite hospitality. A handful of British missionaries stayed back, not for profit but for purpose. Another exception was BBC correspondent Mark Tully, who passed away on January 25.

Today, no British citizen seeks Indian citizenship. Britain, in fact, struggles to control the influx of Indians. Donald Trump recently deported Indians attempting to settle in the United States using fake papers. People migrate from poor countries to rich ones, not the other way around.

Assam's performance on literacy, women's literacy, infant mortality and maternal mortality is among the worst in India. On several of these indices, Bangladesh is far ahead of Assam. So why would a Bangladeshi infiltrate into India—hoodwinking the BSF, the Indian Army and the Assam Police—merely to earn ?5 pedalling a cycle-rickshaw?

With elections approaching and little to show by way of governance, the communal cauldron must be kept boiling. And so, "Miyas" are abused left, right and centre—not because they are the problem, but because they are convenient.

There are broadly two kinds of people in public life, as in private life. One, those who are capable of admitting a mistake, correcting course and moving on. The other consists of those who defend their actions, no matter how overwhelming the evidence against them is. It is this second category that corrodes institutions, hollows out democracy and normalises cruelty. Alas, Sarma belongs to this category.

Cornered by criticism and legal action, Sarma claimed that even the Supreme Court had described those he referred to as "Miyas" as infiltrators. That is simply not true. The Supreme Court has never spoken of a demographic imbalance in Assam in the manner Sarma suggests, nor has it given political sanction to the language of collective suspicion he so freely deploys.

Much of this mythology traces back to a controversial report submitted decades ago by Assam Governor General SK Sinha. He was an unusual figure. He once claimed that he joined the British Indian Army with the intention of wrecking it from within. When he was superseded, he left the service and began taking positions that conveniently aligned with the Opposition of the day. In doing so, he proved only one thing—that he was unworthy of the uniform he once wore.

Sinha's report warned of large-scale infiltration from Bangladesh that would allegedly alter Assam's demographic profile. The Supreme Court did take note of the existence of this report. But it never endorsed its conclusions. There is a critical difference between referencing a document and validating its worldview. Sarma, like many before him, has chosen to erase that distinction.

The Chief Minister made another atrocious claim: that "Miyas" call themselves "Miyas," as though self-reference legitimises abuse. History offers countless examples that expose the fallacy of this argument. In the United States, Black Americans were once referred to as "Negroes," while "nigger" functioned as an openly abusive term. Members of the community may, at times, have used these words among themselves. That never legitimised anyone else using them as labels of subjugation. Power decides what is permissible, not semantics.

Closer home, Kerala offers a painful reminder of how casually discrimination once operated. A backward community was known by a particular word, now unspeakable. We had a neighbour whom everyone called "Krishnan Cho***n". He never objected. Social conditioning had taught him that objection was futile. Today, no one would dare to address a person from the same community by that name. Society changed not because the word changed, but because conscience did.

I once covered a massacre in Bihar that was triggered primarily because a Dalit man dared to give his newborn the same name as a landlord's daughter. In many parts of India, Dalits were not even permitted to name their children after Hindu gods and goddesses.

A few years ago, a two-term BJP Member of Parliament narrated, with pride, that he always carried a glass in his bag. Whenever he visited a Brahmin household, he would be offered water or tea in his own glass. "This is our tradition," he said, as though oppression, when ritualised, becomes culture. That such stories are told without shame tells us how deeply normalised exclusion remains.

Ordinarily, a CM who publicly spreads hatred and instigates people to act outside the law should have been asked to step down. Sarma is believed to have violated multiple provisions of the Amit Shah-piloted Bharatiya Nyay Samhita. These are not minor infractions. They strike at the heart of constitutional morality.

Instead of introspection, Sarma chose intimidation. He threatened to "teach Harsh Mander a lesson," declaring that hundreds of cases would be filed against the former IAS officer. The message was clear: dissent will be punished, compassion criminalised.

Who could have acted against Sarma? Only one person—the Prime Minister. But how does Modi summon the moral courage to punish Sarma when he himself was the first to use the word "Miya" in this political sense? What has Sarma done that Modi has not done earlier, and with far greater impact?

In the last Lok Sabha elections, Modi referred to Muslims as infiltrators, as people who produce children endlessly, as those who would snatch the mangalsutra from Hindu women. It is impossible to recall a more sustained hate speech by a sitting Prime Minister. Amit Shah, for his part, famously described "infiltrators" as termites. When the language at the top is so toxic, how can restraint be expected below?

Contrast this with another moment in recent history. During Operation Sindoor, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh approved the appointment of a Muslim woman officer to brief the media on the progress of the operation. Colonel Sofia Qureshi performed her duty with quiet professionalism. She won the admiration of the nation not because she was Muslim, but because she was an Indian Army officer for whom the country mattered more than life itself.

Yet even that moment could not escape bigotry. A Minister in Madhya Pradesh made derogatory remarks about Colonel Qureshi, calling her a "sister of terrorists." Eight months have passed since an FIR was registered against him. No action has followed. On the Supreme Court's direction, the state constituted a Special Investigation Team, but it has not been given the sanction to prosecute the Minister.

Imagine, for a moment, the roles reversed. Imagine a Muslim public figure making a similar derogatory statement about Wing Commander Vyomika Singh of the Indian Air Force, who stood alongside Colonel Qureshi. He would have been counting the bars of a jail cell by nightfall, and chances are his house would already have been reduced to rubble by a bulldozer.

I am as curious as anyone to see how the Supreme Court will uphold justice in this case. The Court has the power to take suo motu action when constitutional authorities instigate hatred or violence against fellow citizens. Whether it will do so is another matter altogether. Perhaps expecting consistency is asking for too much.

George Orwell once warned us: "The further a society drifts from the truth, the more it will hate those who speak it." In today's India, that drift seems not accidental, but carefully engineered.