.jpg) Patrick Crasta

Patrick Crasta

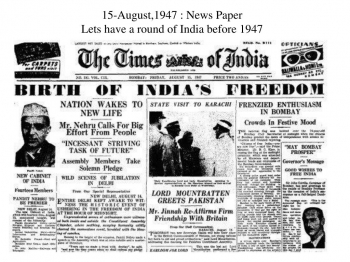

Of those who lived and savoured life in pre-independence India, we have not many. For, one should be at least 17 years old at the time of freedom to say he has experienced life in pre-independent India. Such a person would be 92 now. And I just qualify.

I joined the British Indian Army in July 1947 and India became independent in August. When I boasted this to my friends, they said, “With soldiers like you, the British must have realised they would no more be able to continue their rule of India.”

Though intended jokingly, there is truth in what they said. The civilians spearheaded by the Indian National Congress continued their non-violent struggle for decades. Gandhiji asked the British to quit India in 1942. Instead of quitting, the British put all Congressmen in jail and continued their rule even when they were engaged in World War II fighting the formidable powers of the Axis – Germany, Italy and Japan.

The British won the war. But their power in India shook when the instrument of keeping India under their rule, the British Indian armed forces, started revolting. The Indian soldiers in Malaya who surrendered to Japan regrouped under Subhas Chandra Bose and fought the British under the name of the Indian National Army (INA). Though they surrendered when Japan was defeated in the war, their trial by the British evoked a lot of opposition among Indians, especially the armed forces. Indian Navy sailors in Bombay and other places revolted and marched along the streets. In the Air Force stations, airmen refused to take orders from British officers.

An extract from a dispatch sent to King George VI by the Viceroy Lord Wavell stressed this point. “The Last three months have been anxious and depressing… Perhaps the best way to look at it is that India is in the birth-pangs of a new order, the most disturbing feature of which is the unrest beginning to appear in some units of the Indian Army.”

All this is to dispel the impression that it is the struggle by the Congress alone that brought freedom. No doubt, it is the Congress to which the British passed power. Jawaharlal Nehru became the Prime Minister and other Congress leaders, the ministers.

As for my role in the armed forces, it had its roots in sheer necessity. I was from a village in the princely state of Cochin, now a part of Kerala. The war years were hard on all of us. While farming families could survive by selling their rice and keeping some for their own consumption, heads of families like my father, a government servant with a salary of Rs.10, struggled. As the only one in the village who could read and write English, I earned some welcome pocket money reading letters for my fellow villagers from their loved ones in far-away places. These inconsistent earnings sometimes financed my lunches on school days, otherwise I did without. But once I passed Matriculation and there was neither scope for going to a college nor sign of a job, I was impelled to entrain for Madras to try my luck there.

Becoming an uninvited guest at the home of a relative in Madras, I walked the city streets in search of a job. My Matriculation certificate and my English speaking ability might have opened opportunities for me, but my sunburnt look, barefooted in a dhoti and shirt, ensured that all the posh office doors stayed firmly shut.

One day I came across the Army recruiting office. The Havildar looked me skeptically up and down, but I was duly taken to the medical officer, since matrics were a rarity in those days. Though I was underweight, the recruiting officer declared this shortcoming could be made up. I was enrolled and ordered to entrain that very evening for Ferozpore in Punjab by the military special. I informed my host, picked up my bag, boarded the spacious train with my fellow recruits, and started a new journey in life.

Within two months, India too started its new journey as an independent nation.

The Indian Army is a nursery where diversity dissolves into unity. We ‘Madrasis’, who had once mistaken the chapatis served in the mess for thick papads, eventually learnt to relish roti-sabzi. Not just that, we marched proudly in line with our fellow soldiers, all of whom imbibed integration into their very beings. But within days of beginning our training at Ferozepur, India dissolved into violent disunity.

Hindu-Muslim riots erupted in the town. We freshers were ordered to march through the streets to maintain peace, rifles on our shoulders. It mattered not an iota that we had no ammunition and even less idea how to load it. Our appearance was apparently enough to restore peace.

It was through my friend Abdul Kadar, the only Muslim in our group, that I perceived the essence of secularism. In those days, the Muslim soldiers had to decide whether they were going to continue in India or become Pakistani citizens. Abdul was from Calicut (now Kozhikode, in Kerala) and I was sure he would not exchange the home, culture and language he knew for the promised land of the Muslims. When he returned from the Training Centre Headquarters after giving his option, we all waited for his answer.

“The country of Muslims,” he informed us.

“Pakistan?” We thought this strange. He had never shown any particular interest in religion till now.

“No,” he replied.

“Hindustan?”

“No.”

To his perplexed listeners he explained, “There was no option for Hindustan. I opted for India which is the Motherland of Muslims too.”

And so from fine characters like Abdul Kader and others I met over the years, I continued to learn and grow. My career, begun as a “sepoy clerk” at the birth of India, progressed. By the time I retired in 1973 as a Subedar Major, India was 26 years old. And now it has stepped into its 75th year. Innumerable events have taken place in between, too many to pen down in this space.

Did freedom bring changes for the better? Yes. India became an industrial force with setting up of factories, building dams and electric powerhouses. Agriculture developed to make the country self-sufficient in food. Education made big strides with the building of schools and colleges. Healthcare got a fillip by setting up of ultramodern hospitals.

However, one dismal feature of India remained: Poverty. When millionaires became billionaires, the poor became poorer. They had to move from villages to cities for work. When there was no work in cities, they had to walk back kilometres to villages. There too they had no work and moved back to the cities. Thus a section of the poorest of the poor emerged — the migrants.

And freedom for the people? As an ex-soldier I would rather be apolitical. I simply quote the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court regarding the existence of the sedition law in the statute. Expressing concern over its misuse, he sought to know if this colonial law is still needed 75 years after Independence.

75 years of Independence was good. It could have been better.