.png) John Dayal

John Dayal

.jpeg)

The Union Budget for 2026-27 is being formatted even as we write, and will be presented on February 1 in the Lok Sabha. The Budget Session of Parliament will commence from January 28 and will continue till April 2.

The budget is prepared based on recommendations and demands from various ministries, including the secret demands of the Defence and Home ministries. Added to these are the government's own political priorities, the needs of the ever-hungry Prime Minister's Office, and the projects and schemes of the state governments in which the Centre has a stake.

But since the eclipse of the earlier united democratic government, with Mrs Sonia Gandhi as the Chair of the coalition and Mr Manmohan Singh as Prime Minister, when the Ministry of Minority Affairs came into its own, minorities have been all but invisible in the budget.

Even in the crumbs that fell off the Union's table after Mr Narendra Modi came to power, Christians got a pittance, their deprivation becoming painful when the large-scale cancellation of the FCRA licences - an overwhelming number of Church institutions and Christian NGOs shrunk much of their development, welfare and empowerment work, leaving 80% of their staff and collaborators jobless.

Since 2014, the discourse around minority welfare budgets has been contentious. While the government has asserted its commitment to "Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas" (Together with All, Development for All), budgetary data and policy outcomes tell a more complex story - particularly for Christians who constitute approximately 2.3% of the population.

The lack of transparent, community-level budget data is a nuisance for researchers and media reporters and also hinders accountability and targeted policy interventions.

Despite nominal increases in early years, real spending on minority welfare has declined sharply since 2021. This is reflected in under-utilisation of funds, sharp cuts to education schemes, and stagnation of infrastructure development projects.

The total cumulative allocation for minority welfare over ten years is approximately ?40,000-45,000 crore, but this masks a post-2022 contraction of over 30%, contradicting government claims of empowerment.

Christians face a "double whammy". They receive a disproportionately small share of minority welfare budgets and have lost significant support due to FCRA de-registration of NGOs that provided critical grassroots services.

The combined effect is reduced scholarship access, closure or downsizing of educational and social institutions, limited infrastructure development in Christian-majority districts, and finally, heightened vulnerability amidst rising incidents of religious violence.

After intensive lobbying by community groups, including the All India Catholic Union, with the government and with the Congress high command, the Ministry of Minority Affairs (MoMA) was established in 2006 to address the socio-economic challenges of minorities - Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, and Parsis - which are named in the National Minorities Commission Act.

The Indian Constitution, as such, neither names religions nor defines religion. Religion figures in laws such as the Hindu Code, the Marriage and Succession Acts, and the Hindu Undivided Family Act, which provides preferential tax treatment.

The ministry's key functions included administering scholarship programmes, skill development schemes, infrastructure projects under the Pradhan Mantri Jan Vikas Karyakram (PMJVK), and cultural preservation.

Between 2014-15 and 2024-25, nominal budget allocations to MoMA rose from approximately ?3,200 crore, peaking around ?5,000 crore in 2022-23 before sharp cuts and under-utilisation set in.

When accounting for inflation—averaging roughly 5.5% annually—the real value of the minority welfare budget shows stagnation or decline. Early years (2014-19) saw real-term maintenance or slight growth, but from 2020 onwards, despite modest nominal increases, actual spending power diminished.

By 2024-25, the inflation-adjusted budget hovers near ?2,600 crore in 2014-15 rupee terms, representing a significant real-term contraction compared to the 2014-19 average of over ?3,500 crore.

Scholarships constitute the largest single category of minority welfare expenditure, critical for educational retention and advancement among minority youth. Major programmes include Pre-Matric Scholarships, which support students up to class 10, followed by Post-Matric, and Merit-cum-Means Scholarships.

Two very good ones were the Maulana Azad National Fellowship (MANF), which supported research scholars from minority communities, and the Padho Pardesh support for minorities pursuing education abroad.

Scholarship allocations grew steadily until 2018-19, reaching nearly ?1,900 crore. However, post-2019, these funds faced severe cuts. Pre-matric scholarships declined sharply from ?1,425 crore in 2021-22 to ?433 crore in 2023-24. Merit-cum-means scholarships fell from ?365 crore to ?44 crore in the same period.

The MANF was scrapped in 2022, affecting approximately 6,700 research scholars. And finally, the Padho Pradesh scheme was discontinued without replacement.

These reductions have had an immediate impact on beneficiary numbers and educational outcomes. For instance, the total number of scholarship recipients declined from 67.3 lakh in 2019-20 to 62.6 lakh in 2021-22, reflecting both budget cuts and under-utilisation.

Add to that the disincentive the New Education Policy gives to higher education, favouring an outflow over employment-oriented training, and the cumulative penalty on bright and aspirational students from poor families can be described as catastrophic.

Christians, despite constituting 2.3% of the population, had received disproportionately fewer scholarships relative to other minorities, especially Muslims, who account for about 14% of the population and received 80-90% of the benefits, as also alleged by the Church leadership.

Statistics are scarce, but available data suggest that Christian students benefit from only 1 to 5% of scholarships. In 2021-22, they accounted for less than 2% of pre-matric scholarship recipients, and in skill development schemes like Seekho Aur Kamao, they accounted for fewer than 1%.

This under-representation occurs despite Christians having better overall educational indicators in some regions.

The worst blow to minority welfare, especially for Christian NGOs, was the wildly sweeping cancellations of the licences or permits to receive foreign donations under the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) governing all foreign funding to Indian NGOs. Among them were thousands of large and small Church-related NGOs that played vital roles in education, health, and social welfare.

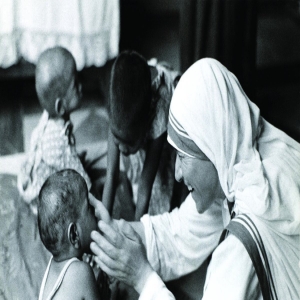

The Home Ministry's brutal action spared no one. Mother Teresa's Missionaries of Charity was the most prominent one. An international uproar persuaded the Modi government to restore the MC sisters' FCRA, benefiting thousands of orphan infants they had picked up from garbage dumps or who had been left at their ashrams, and the dead and the dying whom the Sisters nursed with much love.

Many NGOs had to reduce or terminate projects due to funding. Some Christian schools, healthcare centres, and community service providers shut down. Outreach was drastically diminished with reduced capacity to supplement government welfare schemes, especially in underserved tribal and remote areas.

The Pradhan Mantri Jan Vikas Karyakram (PMJVK) aims to improve infrastructure in minority-concentrated districts, including schools, roads, and community centres. Its funding increased from ?113 crore in 2014-15 to around ?400 crore by 2023-24, a rise, so to speak, but limited in scale.

In Christian-majority districts, especially in the Northeast, the allocation remains tokenistic relative to the need.

The money spent on minorities seems a drop in the ocean when seen in contrast to the open and hidden expenditure on Hindu welfare and pilgrimage infrastructure, which has surged dramatically.

Following the 2019 Supreme Court verdict, Ayodhya has seen over ?1,000 crore allocated for the construction of the Ram temple, including urban renewal and pilgrimage infrastructure.

In Varanasi, which is also the Lok Sabha constituency of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, investments of over ?4,000 crore have been made, including in Smart City initiatives and Namami Gange.

The government does not see these expenditures as connected with the majority religion. In the same manner, the Kumbh Mela sees Centre and state infrastructure investments for the 2019 and subsequent events running into thousands of crores for sanitation, transport, and safety, which do not carry a religious tag.

The ecologically very controversial Char Dham Highway Project in the Himalayas, with a budget exceeding ?12,000 crore to connect Hindu pilgrimage sites, is not deemed to have a religious angle.

Taxpayers' money spent on Mathura, Vrindavan, Somnath, and other pilgrimage centres for temple restoration, tourist facilities, and urban infrastructure is jointly funded by the Centre and State governments, reflecting a coordinated and well-resourced agenda.

This disparity highlights a shift in budgetary priorities aligned with the government's ideological leanings, raising concerns over the secular and inclusive character of state policies. It also signals shifts in India's social contract.

The marginalisation of minorities, especially Christians, runs counter to constitutional guarantees of equality and cultural autonomy. State governments that are favourable to the religious minorities cannot adequately compensate for this shortfall.

Increasing budgetary focus on Hindu religious infrastructure aligns with the BJP's ideological agenda but risks alienating minority communities.

Rising incidents of anti-Christian violence, coupled with shrinking welfare budgets, exacerbate social tensions.

This is more than what the nation and the community have budgeted for in their acceptance of the secular and federal Constitution.